To Share or Not to Share? (Part 3 of 3)

Part Three of Three: Uninterrupted Work and Concentration in the Montessori Classroom

In Part One of this blog post series, we discussed our concerns with the conventional view that sharing is an inherent virtue. We differentiated between voluntary sharing for mutual gain, and surrendering under the threat of compulsion. We suggested that adults should not pressure or even encourage children to share on demand, but should instead protect their right to uninterrupted play. In our view, this approach encourages children to view other children as potential playmates, rather than threats, and results in an attitude of genuine goodwill and benevolence towards others.

In Part Two of this series, we offered up some guiding ideas for practicing voluntary sharing at home. We emphasized the importance of prevention, of setting up a carefully prepared environment—human and physical—that enables children to interact peacefully and respectfully with each other, instead of squabbling about toys.

Part Three discusses how we handle sharing in our Montessori classrooms, and the role our clear roles play in fostering both a peaceful community, and an environment that enables children to achieve the deep concentration they need to learn successfully.

Sharing in a Montessori Classroom Environment

“The child’s body lives also by joyousness of soul.”

—Dr. Maria Montessori

In our Montessori classrooms, instead of sharing on demand, we teach children to take turns—similar to a library model, where many people, in succession, use the books.

Here are our simple Montessori classroom rules and how we apply them:

The one material rule. A child may have one and only one activity out at a time. He can take any material he has received a lesson on from a shelf and work with it in a clearly-defined work space, such as a small table or a rug rolled out on the floor. Once he is done, he needs to put the material back in its proper spot on the shelf, before he can move on to his next activity.

The one material rule. A child may have one and only one activity out at a time. He can take any material he has received a lesson on from a shelf and work with it in a clearly-defined work space, such as a small table or a rug rolled out on the floor. Once he is done, he needs to put the material back in its proper spot on the shelf, before he can move on to his next activity.- The taking only from the shelf rule. Children may take materials only from the shelf, not from each other. Even when one child is done with an activity, he can’t just give it to a waiting peer. Instead, he needs to place it back on the shelf. The other child may then take it from the shelf.

- The voluntary interaction rule. Children may work together with one material, if they both choose to do so. If one child has an activity out, another child may ask whether he can join, and the first child is free to accept or decline that request. We also teach children to respect each other’s workspace by, for example, working around and not over the rugs where other children work.

In the beginning of the year, or with a new class, we explicitly explain and model these rules. The teacher reinforces the rules as needed, providing words to children (“Max, I have the pink tower now. You may have it when it’s back on its stand”), guiding children who haven’t yet mastered keeping their hands to themselves (“Susie, you may watch Max working with the Pink Tower. Please stand back with your hands behind your back.”), and redirecting those who need more help (“John, I see you are having a hard time waiting for the buttoning frame. I’ll help you pick another work: would you like to work with the zipper frame, or would you rather paint at the easel?”)

Over time, as a classroom community gets established, the children themselves become empowered to enforce these rules. It’s not at all unusual to see a five-year-old gently remind a younger child to walk around rugs, or a four-year-old explain to a three-year-old that she can have a turn when the spooning work is back on the shelf.

Clear rules, and a respect for each child’s right to work without being forced to surrender the materials, is a key factor in the peacefulness parents observe when visiting our Montessori classrooms. Yet this respect, this refusal to allow one child to interrupt another’s activity, has another, equally important purpose: protecting a child’s right to work enables him to meet his need for mental nourishment, and, in doing so, helps him become a more centered, better adjusted young person.

Clear rules, and a respect for each child’s right to work without being forced to surrender the materials, is a key factor in the peacefulness parents observe when visiting our Montessori classrooms. Yet this respect, this refusal to allow one child to interrupt another’s activity, has another, equally important purpose: protecting a child’s right to work enables him to meet his need for mental nourishment, and, in doing so, helps him become a more centered, better adjusted young person.

Dr. Montessori observed that children are not just physical but also spiritual beings, that they need mental nourishment just as much as food and rest, that just as a hungry child becomes grumpy and disagreeable, so a mentally starved child is prone to misbehave.

The type of deep concentration which Dr. Montessori observed as transformational for children (what modern psychologists have identified as a “flow state”) cannot happen if the child is worried about being interrupted at any minute by another child who may, at will, take away the material he is working with. To truly focus and stretch his mind, a child has to feel safe—not just from physical aggression, but also from unwanted interruptions, whether by adults or other children. As Dr. Montessori put it,

Montessori schools have proved that the child needs a cycle of work for which he has been mentally prepared; such intelligent work is not fatiguing, and he should not be arbitrarily be cut off from it by a call to play. Interest is not immediately born, and if when it has been created the work is withdrawn, it is like depriving a whetted appetite of the food that will satisfy it. (To Educate the Human Potential, p. 80)

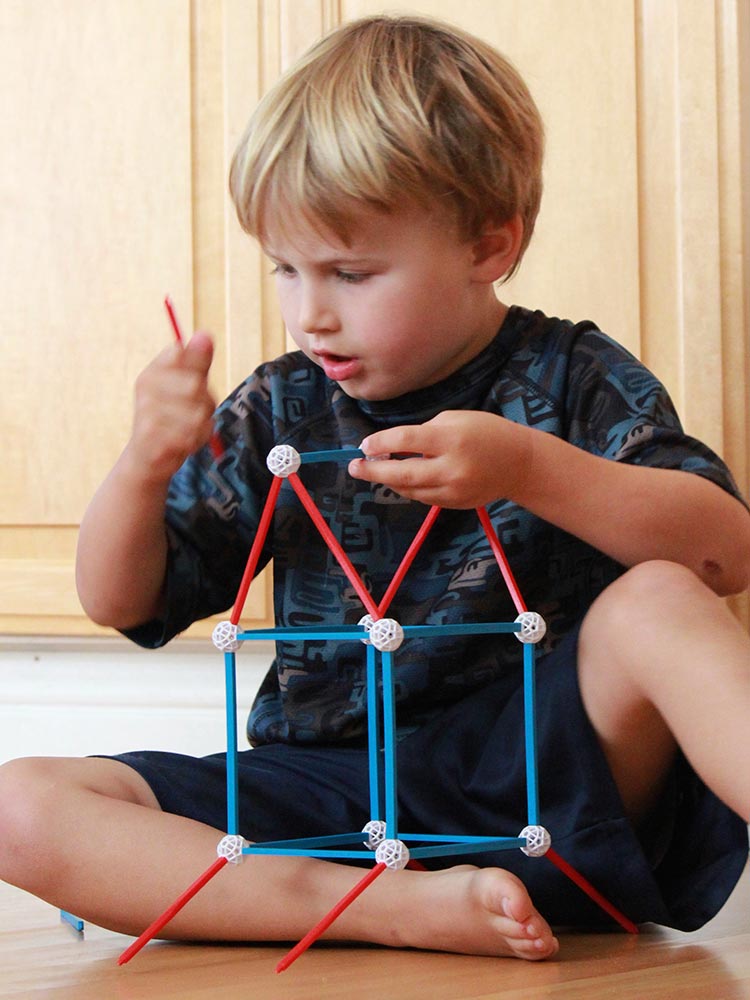

In our Montessori classrooms, we purposefully create a respectful environment where children can fully engage in all kinds of stimulating mental activities. We give them the space and time to tackle “big work”—spending an hour replacing all the knobbed cylinders while blind-folded (without needing to be afraid that another child may make off with one of them!) or passing a whole afternoon writing a story with the small movable alphabet, knowing that in the next morning, the story will still be there to be copied. Montessori children are known for their advanced academic achievements, their ability to write, to read, to do arithmetic before they even enter elementary schools—skills that are honed during child-initiated, uninterrupted working periods.

Ask yourself: would children be able to tackle this type of deep, challenging work if we practiced sharing on demand—as is the case in many non-Montessori day care centers and preschools?

Consider also the subsequent benefits of an environment that protects concentration. Dr. Montessori observed that once children get comfortable in a Montessori environment, once they feel safe and connect with a material, once they concentrate, many common misbehaviors—tantrum, hoarding of toys, uncontrolled and clumsy movement, etc.—disappear:

One of the chief reasons for the spread of our schools has been the visible disappearance of these defects in children as soon as they found themselves in a place where active experience upon their surroundings was permitted, and where free exercise of their powers could nourish their minds. Surrounded by interesting things to do, they could repeat the exercises at will, and went from one spell of concentration to another. Once the children had reached this stage, and could work and focus their minds on something of real interest to them, their defects disappeared. (The Absorbent Mind, p. 199)

Our clear turn-taking rules enable children to feel safe. They allow one child to work, and another to observe. They set the stage for children to concentrate, to help themselves to the mental nourishment their growing brains require. This, in turn, makes them happier, more fulfilled; it supports their mental maturation and health. Happier children are better-behaved children, children who are less likely to act out, throw tantrums, or be overly possessive of classroom materials.

At first glance, the Montessori alternative to on-demand sharing seem counter-intuitive in today’s sharing-focused parenting culture. Yet providing a safe environment, where children can work to their heart’s content free from constant interruptions, actually serves the needs of children. It enables them build their attention spans, to overcome behavioral issues, to develop self-discipline and to master more complex academic materials,. And it ensures healthier, more collaborative peer relationships, and offers a world in which others are not a potential threat, but a potential source of joy.

Be clear on your goal: do you want to encourage voluntary sharing (trading value for value), or do you want to compel children to surrender their toys on demand? Our suggestions in this blog post focus on fostering voluntary interactions to mutual benefit. We want to help children see each other benevolently, to treat one another with respect, and to respect the rights of each child to their things and personal space. If your goals are different, you’ll want to think about different rules than those we outline here.

Be clear on your goal: do you want to encourage voluntary sharing (trading value for value), or do you want to compel children to surrender their toys on demand? Our suggestions in this blog post focus on fostering voluntary interactions to mutual benefit. We want to help children see each other benevolently, to treat one another with respect, and to respect the rights of each child to their things and personal space. If your goals are different, you’ll want to think about different rules than those we outline here. For community toys, support taking long turns.

For community toys, support taking long turns. Protect your child’s rights when needed; otherwise,

Protect your child’s rights when needed; otherwise,  In my family, we have been playing by these rules since my daughter was not quite three, and my son, not quite one: my children have never been compelled to surrender their toys on demand—not at home, not at the playground and not at their Montessori school. Yet they are both very caring, kind, friendly children—children who are quite adept at reading social clues, who can (usually) wait their turn, who speak up for their needs, and who have good relationships with their classmates and strong friendships for their age. Last summer, when we were on an extended play date with my daughter and four other six-year-old girls, one of my daughter’s friends hadn’t brought her bike along. This girl was walking alone as the other four girls were riding along happily on their bikes. After a short while, my daughter—who knew I would never ask her to share her bike—noticed her friend’s sad face and realized the friend felt left out. She got off her bike, took of her helmet, and invited her friend to take a turn.

In my family, we have been playing by these rules since my daughter was not quite three, and my son, not quite one: my children have never been compelled to surrender their toys on demand—not at home, not at the playground and not at their Montessori school. Yet they are both very caring, kind, friendly children—children who are quite adept at reading social clues, who can (usually) wait their turn, who speak up for their needs, and who have good relationships with their classmates and strong friendships for their age. Last summer, when we were on an extended play date with my daughter and four other six-year-old girls, one of my daughter’s friends hadn’t brought her bike along. This girl was walking alone as the other four girls were riding along happily on their bikes. After a short while, my daughter—who knew I would never ask her to share her bike—noticed her friend’s sad face and realized the friend felt left out. She got off her bike, took of her helmet, and invited her friend to take a turn.

And yet, in the reverse situation, the same parents often don’t reinforce the “no taking” principle. Instead of protecting their child’s play, they encourage (and sometimes admonish) their child to give up the toy in question.

And yet, in the reverse situation, the same parents often don’t reinforce the “no taking” principle. Instead of protecting their child’s play, they encourage (and sometimes admonish) their child to give up the toy in question.

Some parents who discover Montessori when their child is four years old are concerned about joining the mixed-age primary room mid-stream. “Will my child be playing catch-up? Some of the other four-year-olds are already reading ”, you might wonder. “I’ve just learned about Montessori, and I see how wonderful this environment could be for my child. She’s already four, though. Did we miss the boat?”

Some parents who discover Montessori when their child is four years old are concerned about joining the mixed-age primary room mid-stream. “Will my child be playing catch-up? Some of the other four-year-olds are already reading ”, you might wonder. “I’ve just learned about Montessori, and I see how wonderful this environment could be for my child. She’s already four, though. Did we miss the boat?” It is true that younger is better when it comes to joining a Montessori program. Starting as a toddler or a young three-year-old gives children the best opportunity to benefit from the enriched, carefully prepared classroom environment. As Montessori educators, we understand that the time between birth and age six is the most critical in a human being’s development. During this stage of growth, children go through rapid changes and develop the most important aspects of their personality and intellect.

It is true that younger is better when it comes to joining a Montessori program. Starting as a toddler or a young three-year-old gives children the best opportunity to benefit from the enriched, carefully prepared classroom environment. As Montessori educators, we understand that the time between birth and age six is the most critical in a human being’s development. During this stage of growth, children go through rapid changes and develop the most important aspects of their personality and intellect. While some of these sensitive periods begin at birth, four-year-old children are still in the midst of this amazing time. We regularly see four-year-olds join our class and become drawn to the materials on our shelves; they quickly begin “working” and become acclimated to their new environment. With the right support at home and at school, you’ll be surprised by how much joy both you and your child will get from his Montessori experience!

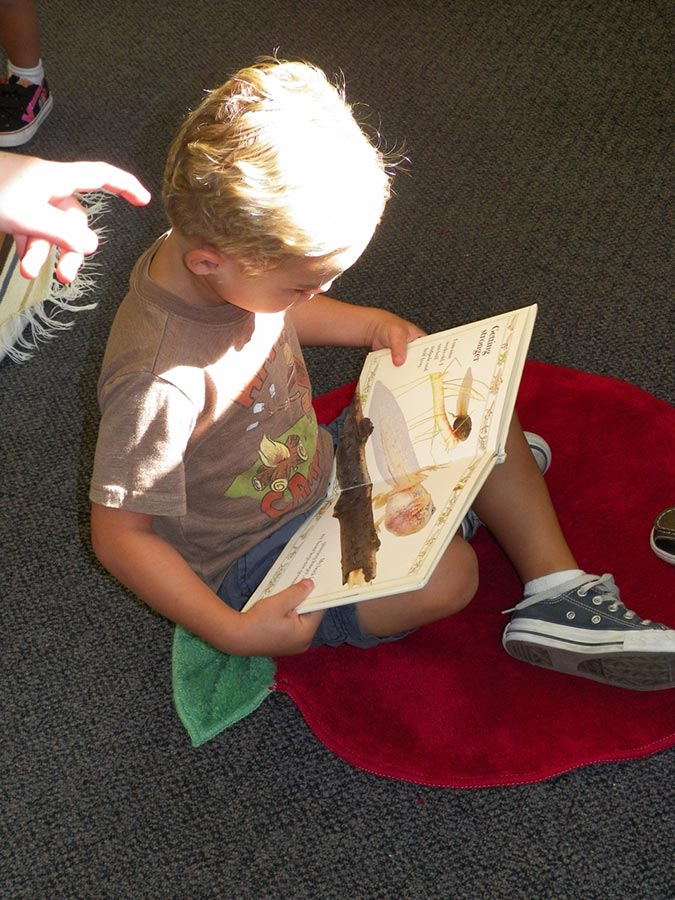

While some of these sensitive periods begin at birth, four-year-old children are still in the midst of this amazing time. We regularly see four-year-olds join our class and become drawn to the materials on our shelves; they quickly begin “working” and become acclimated to their new environment. With the right support at home and at school, you’ll be surprised by how much joy both you and your child will get from his Montessori experience! This consistent time is especially important for your four-year-old who is new to Montessori. Dr. Montessori observed that many issues that children struggle with, from temper tantrums to uncoordinated movement, from disobedience to physical aggression, disappeared when children are allowed freedom in an environment suited to their needs. Often, a child would find some activity that spoke to him, become immersed in it, and repeat it over and over again. Once a child connected to an engaging activity, he became happier, more curious to explore more learning materials in class, and even became kinder and more benevolent to his peers.

This consistent time is especially important for your four-year-old who is new to Montessori. Dr. Montessori observed that many issues that children struggle with, from temper tantrums to uncoordinated movement, from disobedience to physical aggression, disappeared when children are allowed freedom in an environment suited to their needs. Often, a child would find some activity that spoke to him, become immersed in it, and repeat it over and over again. Once a child connected to an engaging activity, he became happier, more curious to explore more learning materials in class, and even became kinder and more benevolent to his peers. The third year in Montessori Primary (the equivalent of traditional kindergarten) is the year when much of the foundational skill development solidifies, and many children suddenly experience huge growth spurts in writing, reading, math and overall confidence.

The third year in Montessori Primary (the equivalent of traditional kindergarten) is the year when much of the foundational skill development solidifies, and many children suddenly experience huge growth spurts in writing, reading, math and overall confidence. The best way to help your child thrive in a Montessori environment is to better understand Montessori yourself. We make this easy for you: When your child joins our program, you’ll receive eight short, one-page handouts explaining key aspects of Montessori, and suggesting simple ways you can align what you do at home with what your child experiences at school. Throughout the school year, we offer Parent Education Events, where we discuss a wide range of topics: from how to support independence to learning math in preschool. Our blog also offers plenty of helpful articles. Your child’s teacher is also a great resource: Our trained head teachers are available via email or in person after school to answer all kinds of Montessori-related questions you may have and to help you understand how you can best support your child.

The best way to help your child thrive in a Montessori environment is to better understand Montessori yourself. We make this easy for you: When your child joins our program, you’ll receive eight short, one-page handouts explaining key aspects of Montessori, and suggesting simple ways you can align what you do at home with what your child experiences at school. Throughout the school year, we offer Parent Education Events, where we discuss a wide range of topics: from how to support independence to learning math in preschool. Our blog also offers plenty of helpful articles. Your child’s teacher is also a great resource: Our trained head teachers are available via email or in person after school to answer all kinds of Montessori-related questions you may have and to help you understand how you can best support your child. One of the beauties of Montessori is the profound respect for the individuality we give each child. Montessori teachers do not compare their students with each other. We know that your four-year-old may need some time to get used to his new school, and that it would not help at all to compare him to other four-year-olds who had started before him. Each Montessori teacher allows her students to develop at their own pace, and she trusts that the Montessori classroom will enable her students to reach their individual potential at their own unique pace.

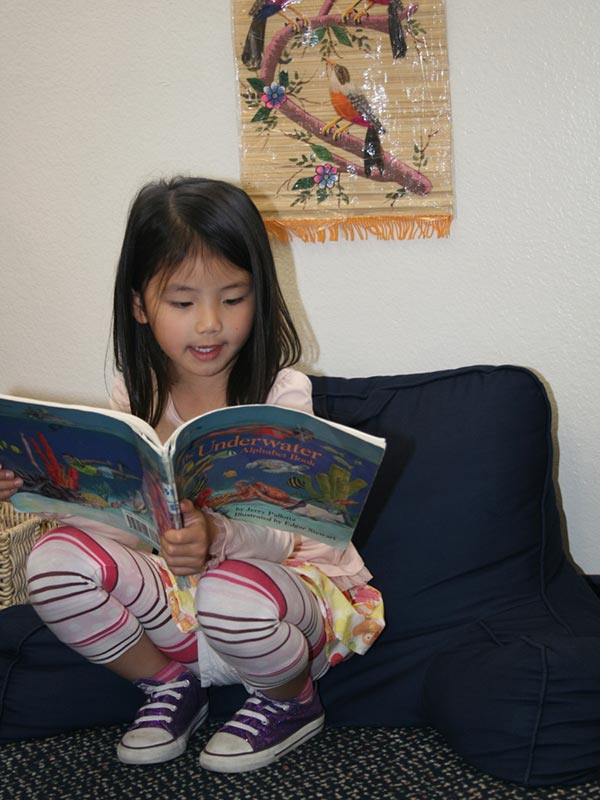

One of the beauties of Montessori is the profound respect for the individuality we give each child. Montessori teachers do not compare their students with each other. We know that your four-year-old may need some time to get used to his new school, and that it would not help at all to compare him to other four-year-olds who had started before him. Each Montessori teacher allows her students to develop at their own pace, and she trusts that the Montessori classroom will enable her students to reach their individual potential at their own unique pace. If you want to support your child’s academic development, the best way to do this is to read with your child. Read a lot! Read a variety of books, discuss what you read, ask her questions about what you’ve read, follow along with your finger under text as you read, and explain vocabulary. That way, when she does finally master her letter sounds, she’ll be able to move along much faster. Find suggestions for

If you want to support your child’s academic development, the best way to do this is to read with your child. Read a lot! Read a variety of books, discuss what you read, ask her questions about what you’ve read, follow along with your finger under text as you read, and explain vocabulary. That way, when she does finally master her letter sounds, she’ll be able to move along much faster. Find suggestions for