How do you develop social skills in preschool?

For many parents, “socialization” is one of the most important goals of sending their children to preschool. But what exactly do we mean by socialization? And what preschool environment helps children learn good social skills, rather than pick up bad ones?

As a parent, you are right to be concerned about socialization. There is evidence that the wrong preschool environment can actually be detrimental to social skill development, causing children to become stressed out by too much, too complex peer interaction.

It turns out that just exposing your child to interactions with peers in preschool is not a magic bullet to develop social skills. In fact, same-age peers, left to their own devices, are not good teachers. As Gwen Dewar, a biological anthropologist, explains:

You do need people to learn people skills. The question is–which people? Preschoolers need to learn empathy, … patience, emotional self-control, social etiquette, … and an upbeat, constructive attitude for dealing with social problems.

These lessons can’t be learned through peer contact alone. Preschools are populated with impulsive, socially incompetent little people who are prone to sudden fits of rage or despair. These little guys have difficulty controlling their emotions, and they are ignorant of the social niceties.

Yes, preschoolers can offer each other important social experiences. But their developmental status makes them unreliable as social tutors. A child who copies other children may pick up good habits–but she may also pick up bad ones.

Gwen Dewar

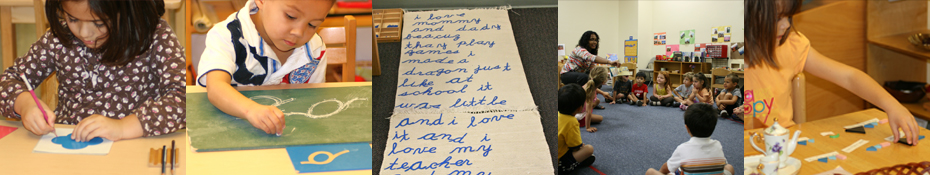

That’s why, in our view, helping a child develop social skills in preschool needs to be approached as thoughtfully and deliberately as teaching him reading or math. That’s why social skill development is purposefully integrated into every aspect of our Montessori preschool classrooms. It is woven into the fabric of what we do, from morning greeting routines to the rules for who can work with a material and when; from the way a preschool teacher models lunch-time manners to the way we guide students to sit attentively during circle time.

Developing strong social skills, to us, means appreciating the value other people bring to our lives, dealing with peers and adults fairly (both one-on-one and in group settings), developing the grace and courtesy skills necessary for mature interaction, and developing a basic benevolent attitude towards people.

For this newsletter, we want to highlight two specific areas of social skills learning which happen in our preschool classrooms, “Grace and Courtesy” skills, and social behavior in the classroom.

-

- “Grace and Courtesy.”

This Montessori term refers to a number of specific lessons, large and small, which we give to our preschool students to help them interact maturely and politely with each other and the adults in their world. Grace and Courtesy lessons cover more than just manners. They equip our young charges with the tools they need to grease the wheels of social interaction. We explicitly show preschool children how to interact through modeled lessons, as well as through our own general example, and we encourage children to practice these skills daily. For example:

- Greeting someone–by shaking hands and saying “good morning,” while ensuring proper eye contact.

- Requesting help constructively–by approaching a teacher, gently making her aware of one’s presence, then waiting patiently until she has completed her current task and is able to respond. Students apply the same lesson when asking more experienced peers for help. They also learn how to politely say “no” when they are asked for help and cannot (or may not want to) give help at that time.

- Giving and receiving compliments–how to notice something well done or a nice behavior, and appropriately compliment the doer; how to graciously receive and respond to compliments.

- Apologizing appropriately–learning to acknowledge a mistake or a slip in behavior, and to sincerely apologize and make amends to young friends and teachers.

- Expressing emotions using words–from the toddler years onward, we teach our students to identify and name their emotions, so they can communicate and deal with their feelings without lashing out at others.

- Table manners–from chewing with one’s mouth closed, to politely asking for seconds at snack time; from answering “yes, thank you” or “no, thank you” when offered a snack, to handling utensils appropriately: nothing that happens at snack or lunch time goes unobserved. Our teachers are constantly on the lookout for the opportunity to impart new skills to our students.

- Social Behavior in the Classroom.Imagine the potential for chaos in a preschool classroom in which up to 24 young children work together simultaneously on numerous diverse activities, each child allowed substantial freedom of movement. This chaos simply does not exist in our Montessori preschool rooms. This is because preschool children learn to follow certain conventions and rules of conduct. Modeling these group and classroom behaviors is an important aspect of a teacher’s role, especially early in the school year. It is also a skill set that is essential to your child’s success, both in further schooling and in life. Whether it is a 7-year-old who needs to raise his hand in a group discussion in a classroom, or a 20-year-old who needs to know how to speak up appropriately during a work discussion, learning to interact maturely in a group setting is a critical life lesson.

- Circle Time.

While the majority of the work in a Montessori preschool classroom happens individually or in small groups, we incorporate some whole class activities, such as singing, joint read aloud and perhaps reviewing the calendar each day.During these group times, we teach our preschool students how to sit cross-legged in a circle with their hands in their laps, so everybody can see and hear the teacher, without being disrupted by a neighbor moving about. We show them how to actively watch a demonstration, and how to attentively listen to the words of others, so they can learn together. We show them how to raise their hands and wait to be called upon before speaking, showing their respect for their peers, and ensuring that they will be heard when it is their time to talk.While it may seem odd at first to see children follow such specific instructions, it is easiest for preschoolers to learn social rules in a simplified, straight-forward manner. Clear rules also make it easier to ensure that each child can participate: a shy child who might not speak up or find a voice in a free-for-all environment, will, over time, learn that he can speak up and will be heard in our carefully designed social environment.

- Individual Work Time.

During the bulk of our preschool day, children freely choose what to work on, and who to work with. All social interactions during these times are voluntary: no child is forced to play with others, to share a toy, or to help a peer. Instead, we set up clear rules to foster respectful, mature, genuinely inclusive interactions, rules which ensure each child’s work, personal space and autonomy are respected by his peers. For example:

- A work need not be shared. In contrast to many preschools, where “sharing” may be a requirement, our approach is different. Once a child picks an activity from a shelf, he is free to work with it for as long as he wants. Another child may ask to join, and he is free to agree or, politely, decline this request. (If he declines inappropriately, he is gently encouraged to reconsider.) Only when the activity is placed back on its shelf may the next child take it. This clear rule, that only material that is on the shelves is available to be chosen, prevents much of the stress-inducing fighting over toys so typically seen in groups of young children–fighting that is absent from our preschool classrooms.

- Work spaces must be respected. One of the first lessons our preschool students learn is to walk around the mats on the floor, where their friends have put out their work. We also show and remind our students to keep their hands to themselves, and not to touch another student’s body or activities without first asking for permission. This is an expression of respect, for the value of the work each child is doing, and for the general concept that a person’s personal space is not to be entered without permission.

- Voices must be quiet, indoor voices. In our preschool classrooms, children are free to talk with each other during their work period. In fact, older preschool children often like to work with friends. To ensure everybody can work, we teach them to speak quietly, and to get up and move across the room, if they want to interact with somebody who is not right next to them, rather than calling to them.

Because social interaction in a Montessori preschool classroom is voluntary, and because the children are encouraged to act toward each other with “grace and courtesy,” a Montessori preschool classroom is the embodiment of a benevolent and civilized social environment. Quoting Dr. Montessori:

As visitors to the Children’s House have noted, [the children] seemed to be “little men” or as others have described them, “senators in session.”

The children are so engrossed in their work that they never quarrel over the objects. If anyone does something extraordinary, he finds someone who will admire and be delighted with his work. No heart bleeds at the good of others; the success of each is the joy and wonder of the rest. And this often creates eager imitators. All seem to be happy and satisfied with doing what they can. The activities of others do not arouse their envy or painful rivalry.

…A little child of three works peacefully alongside a boy of seven and is as contented with his own work as he is about the fact that he is shorter and does not have to envy the older boy’s height…

All this might give the impression that these children are excessively repressed [but] for the fact that they are utterly lacking in timidity. Their bright eyes, gay and disarming countenances, and their readiness in inviting others to observe their work . . . make us realize we are in the presence of individuals who are masters of their own homes.

Dr. Maria Montessori

- Circle Time.

- “Grace and Courtesy.”

It is this benevolent, positive interaction among happy individuals that we seek to foster in our Montessori preschool classrooms, and which we offer to your child, should you choose to enroll him at LePort.

Teachers are guides, not lecturers. They individualize instruction to keep each child optimally challenged. In traditional elementary education, much instruction happens at an all-class level; students generally move through the same curriculum at the same pace. This is more true now then ever, as mandatory standardized testing forces teachers to ensure that all students meet common minimum standards. This approach by definition fails to optimally challenge most of the students, most of the time: a child who is advanced in a subject will be bored; one who is behind will quickly become anxious and concerned about his shortcomings.

Teachers are guides, not lecturers. They individualize instruction to keep each child optimally challenged. In traditional elementary education, much instruction happens at an all-class level; students generally move through the same curriculum at the same pace. This is more true now then ever, as mandatory standardized testing forces teachers to ensure that all students meet common minimum standards. This approach by definition fails to optimally challenge most of the students, most of the time: a child who is advanced in a subject will be bored; one who is behind will quickly become anxious and concerned about his shortcomings.  Children have choices, there’s no one-size-fits all curriculum. Students are encouraged to be curious; they are engaged and love learning. When do you do your best work: when someone makes you do a task, or when you freely choose it? Autonomy is a huge factor in motivation, and Montessori elementary enables children to have a say in their learning. Of course, each child has to learn certain skills; mastering arithmetic isn’t optional. But instead of forcing each child to complete the same worksheet,

Children have choices, there’s no one-size-fits all curriculum. Students are encouraged to be curious; they are engaged and love learning. When do you do your best work: when someone makes you do a task, or when you freely choose it? Autonomy is a huge factor in motivation, and Montessori elementary enables children to have a say in their learning. Of course, each child has to learn certain skills; mastering arithmetic isn’t optional. But instead of forcing each child to complete the same worksheet,