The Fundamental Choice

It is the child who makes the man, and no man exists who was not made by the child he once was. Dr. Maria Montessori

Last May, I had the opportunity to observe a kindergarten and first grade class at the local elementary school my then 5-year-old daughter would have attended in fall, if we went the public school route.

The school I observed is about as good as it gets in public education. It’s a “Blue Ribbon”, “California Distinguished” school, with standardized test scores in the top 5% of the state. It has families all over the city vying for spots. The principal, whom I had the pleasure to talk to at length, is a kind man and a good listener; he struck me as the type of educator deeply dedicated to providing the students in his charge with a quality education.

Generally, public schools are reluctant to allow observations by prospective parents. After I shared that my daughter attended Montessori school, and that I was concerned how she would transition to the public school environment, the principal made an exception to his usual policy and invited me to observe some of his best classes.

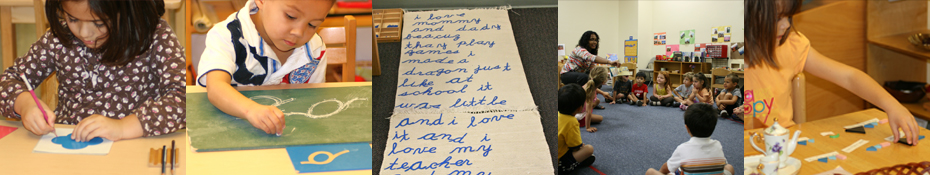

I saw a lot in the time I spent in each of two classrooms. The kindergarten students were working on individual letter sounds q, v, and z. The 1st graders were writing 3-4 sentence paragraphs and working with numbers up to 100. The contrast with a Montessori classroom was dramatic. Kindergarten-aged children in a Montessori environment are reading real books and writing multi-sentence stories in cursive, and elementary 1st year students are writing page-long stories, reading chapter books and doing arithmetic into the thousands.

But while the contrast was dramatic, it wasn’t surprising to me. I went in expecting this difference in academic progress. What really took me by surprise was just how deep the difference between the programs went. The traditional classrooms I observed were, in a thousand ways large and small, training students to conform passively to adult rules and expectations—a completely opposite behavioral mindset than the active-minded independence we encourage in Montessori preschool and elementary programs.

Let me share just two small observations among many, one from each class.

First grade: Teachers as guides or as servants? Children as independent actors, or passive observers?

In the first grade class, the children were studying how seeds grow into plants. Each child was asked to observe how a few lima beans and sunflower seeds germinated, and to record their observations in a science journal—a project that you might well find in a Montessori lower elementary classroom.

But here is how the project was implemented in this classroom: the teacher walked around the tables in the room, stopping by each child. She tore off a paper towel, put it on a plate, and sprayed it with water. She then had the child put the lima beans and seeds on the paper towel. After that, the teacher folded the towel, and inserted it into a zip lock bag, upon which the child had written his or her name. Over the entire 15 minutes I observed, the teacher was occupied making these kits for the children, while children were apparently supposed to be working independently on other tasks, but in fact spent much time chatting and mingling without a clear purpose, as the minutes ticked by. The teacher completed the kits of approximately 6 out of the 30 students in the room, suggesting that she was going to be occupied by kit making for well over an hour that afternoon.

As someone familiar with Montessori rooms, I could not believe that the children had such a passive role! This was a class of 6 ½ to 7 ½-year olds, fully capable (one hopes!) of tearing off paper towels, of wetting them by using a sprayer, of counting out beans and seeds and placing them on a towel, and so on. These children could have and should have made these science kits by themselves! Instead, the teacher did it for them. The teacher was in charge, the students, outside observers of their own education.

I couldn’t help but contrast this with how the same experiment would happen in a Montessori classroom. The teacher might take 10 minutes in the morning, collect a group of students ready for this experiment, and give them a brief introduction, describing the purpose of the work and demonstrating how to assemble the experiment. She would then set up a table with all the materials, and invite the children to make their own kit. The children would autonomously make their own bags, taking turns at the table. They would have ownership of their work, and reinforce many practical skills in the process. They would help each other if one got stuck, with the teacher monitoring from afar to ensure that the peer interaction was to mutual benefit. The teacher would gain over an hour to dedicate to her actual job, helping students learn, rather than spending her time in essentially the role of an unwanted nanny or servant, doing things to children perfectly capable, and almost certainly eager, to do them for themselves.

Kindergarten: Respect for intellectual independence, or conformity and obedience?

In the kindergarten class, I arrived during a silent work period. I was pleasantly surprised at first: after all, independent, engaging, self-initiated work is the core means to develop concentration skills in children!

But when I observed more carefully, here’s what I saw: these 6-year-old children were totally silent. Not one word was spoken. They were glued to their desks, upon which were found things like play dough, simple coloring pages and other very basic activities typically undertaken by 3- or 4-year-olds in a Montessori class. Some children were engaged, but many more seemed bored and disengaged.

And then the work period ended. The teacher turned on the light, and started counting, loudly: “Five, four, three, two, one. All eyes on me!” Without giving children time to process her expectations, she immediately started directing her students: “Sara, put that down. Ian, stop. Look at me, now. Come on class, remember our agreement: when I count, you stop working. Let’s try that again. Put your fingers on your noses, all eyes on me!”

I stood, stunned, as I saw these twenty-odd six-year-olds touch their noses, line up, and stare at the teacher. I cringed as they were ordered to clean up, pronto (“you have three minutes to clean up, then please find your spot on the carpet” and “Peter, you are late, pick up your pace.”)

Compare this scene with the work periods I observe regularly in Montessori classrooms. There, children have 2-3 hours of uninterrupted work time, twice a day. During this time, the classroom is calm, but not eerily silent, as children are free to move about, talk in appropriate volumes as they work with friends, and select from a wide range of stimulating activities much more engaging than play dough or coloring pages.

In such a Montessori room, here’s how the work period might end: the Montessori teacher would ring a small bell, and speak gently in a quiet voice, “Children, I invite you to finish up your work and put it away if you are interested in coming together in circle.” After this request, children are free to complete their activity, and to put it away on their terms. A child immersed in an advanced task might continue with it, even as the other children join the circle and the teacher starts reading a book or singing a song. Another child might leave his work out, with his name badge on it, so he can continue and finish it in the next work period.

Consider the difference. In the public school class I visited, the implicit theme is obedience to adult rules. In practice, students learn to conform habitually and unthinkingly to cues and prompts and commands. In a Montessori class, in contrast, the theme is respect for each individual, and the result is that a child develops the ability to responsibly take care of his own work, learning how to act freely while also considering the needs of others.

I cannot be sure how representative my observations are of public schools in general. As a parent, if you’re considering public school, you should definitely make the time to observe the school and classroom your child would be joining. What I know is that this was a highly-rated school, and the two classrooms I observed were chosen by the principal as examples of what a good public school education can look like.

If what I saw is indeed indicative of a pervasive characteristic of public education (and sadly, I suspect it is), then the implication is that in choosing between a public school and an authentic Montessori school, you are making a choice that goes far deeper than just the difference in academics. You are choosing the type of implicit values that will be emphasized to your child: respect vs. obedience, creativity vs. conformity, active-mindedness vs. passivity.

As Dr. Montessori put it, it is the child who makes the man. I’d encourage you, in judging your child’s future classroom, to ask yourself what kind of man or woman you want your son or daughter to become.

This blog post was originally featured on the Maria Montessori website.

Teachers are guides, not lecturers. They individualize instruction to keep each child optimally challenged. In traditional elementary education, much instruction happens at an all-class level; students generally move through the same curriculum at the same pace. This is more true now then ever, as mandatory standardized testing forces teachers to ensure that all students meet common minimum standards. This approach by definition fails to optimally challenge most of the students, most of the time: a child who is advanced in a subject will be bored; one who is behind will quickly become anxious and concerned about his shortcomings.

Teachers are guides, not lecturers. They individualize instruction to keep each child optimally challenged. In traditional elementary education, much instruction happens at an all-class level; students generally move through the same curriculum at the same pace. This is more true now then ever, as mandatory standardized testing forces teachers to ensure that all students meet common minimum standards. This approach by definition fails to optimally challenge most of the students, most of the time: a child who is advanced in a subject will be bored; one who is behind will quickly become anxious and concerned about his shortcomings.  Children have choices, there’s no one-size-fits all curriculum. Students are encouraged to be curious; they are engaged and love learning. When do you do your best work: when someone makes you do a task, or when you freely choose it? Autonomy is a huge factor in motivation, and Montessori elementary enables children to have a say in their learning. Of course, each child has to learn certain skills; mastering arithmetic isn’t optional. But instead of forcing each child to complete the same worksheet,

Children have choices, there’s no one-size-fits all curriculum. Students are encouraged to be curious; they are engaged and love learning. When do you do your best work: when someone makes you do a task, or when you freely choose it? Autonomy is a huge factor in motivation, and Montessori elementary enables children to have a say in their learning. Of course, each child has to learn certain skills; mastering arithmetic isn’t optional. But instead of forcing each child to complete the same worksheet,