Being an expectant or new parent can be overwhelming. I remember being assailed late in my pregnancy by well-wishers and advice givers who proposed dozens of items I should get before my baby arrived. It was enough to make my head turn and to doubt my own instincts, which yearned for a simpler, less complicated approach to parenthood. I admit I followed most of the advice, even when it seemed counter intuitive. Yet 18 years later, with two almost grown children and Montessori training under my belt, I know for a fact that I did not need all that much. Many of the “must-have” were labeled by misconceptions that did not help my children thrive.

Now, as a parenting consultant and Montessori guide, I help create beautiful Montessori infant environments without many of the staples of a traditional baby registry: No bouncer, no walkers, no exersaucers. No noisy battery-operated plastic toys. No cribs! Not even a high chair in sight! The contrast to the traditional nursery is so stark that it can be disorienting for parents who first enter such an environment.

After regaining their voice, parents often ask, “how do the babies sleep on these low beds, without falling out?” and “where do you feed them?” and “aren’t they getting bored?” Parents are concerned, naturally, about their babies’ well being in a setting that is so fundamentally different from the traditional nursery, the expected, and the norm. Yet once they learn more, once they understand a baby’s true needs at a deeper level, once they observe and experience a Montessori Nido (Dr. Montessori’s term for the prepared Infant Environment, the Italian word for ‘Nest”), they often feel drawn to it, and become eager to modify their own home environments along similar lines.

To understand why a Montessori home environment is so different, it helps to realize that as Montessorians, we view babies as “fully human”—as independent beings, on an active, urgent journey to become masters of their own inner and outer worlds. Our goal is not to entertain or serve babies; rather, we want to respect their inner drive for child-led exploration, and help them do for themselves whatever may be in their own power to do. Our goal is not to make it easy for an adult to feed, clothe and put a baby to sleep. Our goal is not to make the adult’s life easier. Instead, we recognize that, in the words of Dr. Montessori, “to assist a child we must provide him with an environment which enables him to develop freely.”

As a Montessori home consultant, I help families set up the four key areas of the home—sleeping, feeding, physical care and movement—with this principle in mind. These basic areas give the child important points of references, allowing him to figure out what is expected of him depending on where he is in his environment. They help the child feel secure by being able to predict what is coming next. He comes to expect food in one area, a chance to move about in another, and the quietness of sleep somewhere else. Routines, order and consistency along with these simple points of reference are of upmost importance during the first few years of life.

Here’s what these areas look like in a Montessori home:

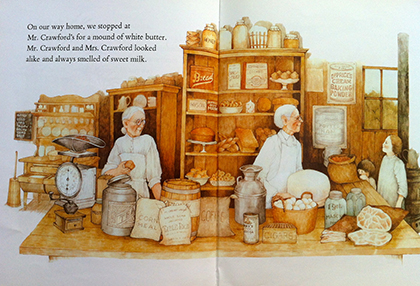

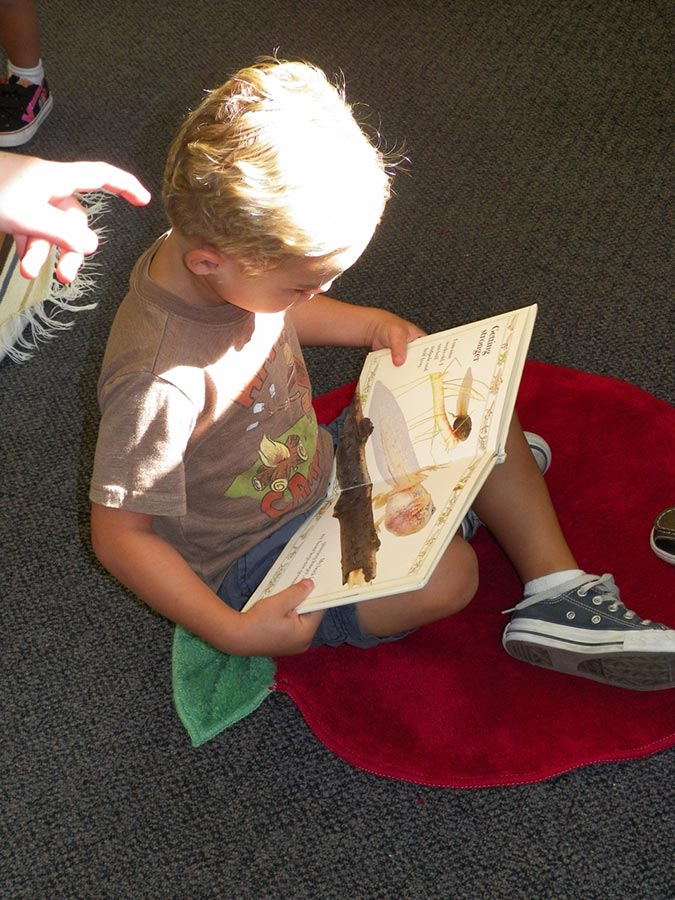

Voila Montessori’s baby-focused nursery designed in collaboration with mollieQUINN. Photo: Laura Christin

The sleeping area is characterized by the absence of one nursery essential, the crib. Instead, we provide a simple low bed (just a mattress on the floor often suffices), along with a Moses basket. The low bed can be any size you choose (crib size, twin, queen etc.), depending on the location and space you have. This “floor bed” will need minimal changes over time if properly set-up as a safe relaxing area for the child. The area should be toy-free with no nearby mirrors: a sleeping place needs to be void of any distractions to help an infant self-soothe, relax and ease into sleep.

“A bed which has enough space to allow for movement and no obstruction

to vision is the first thing to provide in order to assist

the development of voluntary movement.” ~ Dr. S. Montanaro

The floor bed is maybe the most controversial of the Montessori infant suggestions. Parents often wonder, will my child roll off his floor bed, or crawl off and begin to play? Well, that’s certainly the case—but is that an argument against or for the floor bed? By rolling off onto a soft carpet, from the height of a few inches, a child learns to recognize boundaries with little risk. By having the freedom to get out of bed when no longer tired, a child feels empowered, rather than trapped. Think about it from a child’s perspective: wouldn’t such a bed allow a baby to discover something fantastic, namely, that he is in control, that he can get himself to sleep and get himself up again: “I am the master of my movements, I don’t need to stay in my container and cry until somebody rescues me, I can even go to bed when I am tired, no need for me to wait until my sleepy cues have been interpreted.”

The floor bed is maybe the most controversial of the Montessori infant suggestions. Parents often wonder, will my child roll off his floor bed, or crawl off and begin to play? Well, that’s certainly the case—but is that an argument against or for the floor bed? By rolling off onto a soft carpet, from the height of a few inches, a child learns to recognize boundaries with little risk. By having the freedom to get out of bed when no longer tired, a child feels empowered, rather than trapped. Think about it from a child’s perspective: wouldn’t such a bed allow a baby to discover something fantastic, namely, that he is in control, that he can get himself to sleep and get himself up again: “I am the master of my movements, I don’t need to stay in my container and cry until somebody rescues me, I can even go to bed when I am tired, no need for me to wait until my sleepy cues have been interpreted.”

Needless to say, the floor bed requires the adult’s trust in the child’s capabilities and a commitment to letting the child explore her physical boundaries. It means that the entire room a child sleeps in needs to be extremely safe (baby-proofed). So while needing no expensive crib, the Montessori sleeping area requires space and a different type of careful set-up. It may not be easy, but trusting and allowing your child from the very beginning to be aware of their body scheme and physical boundaries will help her on her quest for independence as she matures into a self confident, well adjusted child.

The feeding area is first set-up for the caregiver who is either breast-feeding or bottle-feeding the infant. For the first few months, when babies are dependent on us for food, we should have a comfortable place to feed and bond with them. Keep this area free of any distractions (especially free of TVs and other screens). Feeding is an important bonding time for the child and caregiver. Set up your area so that you have everything you need at arm’s reach, and so that you can sit back, relax and enjoy this precious time that , while exhausting for sure, goes by all to quickly.

“Clearly then the nursing mother should be comfortably seated in a quiet place and feed the child while looking at it. Although it is technically possible to offer the breast and read a book, talk to someone or watch television, we must realize that, in this way, we detach psychological nourishment from biological feeding. As Erich Fromm puts it:

‘We only give the milk but not the honey.’” ~ Dr. S. Montanaro

Later, as the child’s interest in adult foods develops and he becomes capable of sitting upright unassisted, Dr. Montessori recommend a small weaning table and chair, especially for snacks or meals the child takes separately from the parents or other caregivers. These low chairs and tables allow children to independently seat themselves, instead of being lifted up and strapped in. They allow children to sit and have a meal with others of similar ages. They make it possible to set a pretty table, with small, open glasses and real ceramic plates, as a low drop is much less likely to lead to broken china than a drop from an adult-height table.

For meals taken together as a family, I find chairs such as the Tripp Trap a great alternative. These chairs allow an older infant to sit at the table with the family, instead of being pushed back in their own high chair with a tray. Seated at the family meal table, the baby can again have access to a plate, glass and utensils (which often barely fit on a high chair tray). Thus joined at the table, meals are a time for bonding and social relationships. They become a learning opportunity, as adults model proper cultural etiquette using real utensils, real glass cups and plates, and adults are fully engaged and present with children at mealtime. It is important to keep distractions such as iPads, phones or TVs away from this important meal-time ritual.

The physical care area—which includes diaper changing and getting dressed—is designed to facilitate care giving as an opportunity to interact. I highly recommend a changing table in European style, where you face your baby directly, rather than one of the typical US design, where you baby lies perpendicular to you. Being able to look your baby in her eyes as you change her, being able to talk to her and interact with her, is critical to make changing diapers not a drudge and chore, but an opportunity for bonding and learning. Make sure you have all the critical supplies close by, so you can give your child your undivided attention, so you can explain to her what you are doing, and ask for her active participation—such as lifting a leg or pushing an arm through a sleeve.

Only when we become able to give maternal care with the child’s

collaboration are we really doing things ‘with the child’ and not ‘to the child’. ~ Dr. S. Montanaro

While I recommend that changing tables be set up in the bathroom from the start, space may not allow that in all cases. Once children become mobile (strong crawlers or cruisers), I recommend moving diaper changes into the bathroom. Often, a pad on the floor is a good step; as the child can get to it herself, rather than being lifted (sometimes against her will) onto a high surface. Once a baby can stand well, you have the option of doing diaper changes standing up. It helps to provide a grab bar of some kind. If you want to go fancy, you can place it in front of a mirror, so the child can see what happens when you change her and clean her up.

If space permits, I recommend setting up a “care of self” area in the bathroom, too. This area can include a low shelf or table, upon which is placed a basin of water and a small piece of soap for hand washing, along with a little towel for drying. It’s not too soon toward the end of the first year to offer a small potty, along with a bucket for soiled clothing and a basket for clean clothes to switch into.

With this careful preparation, toilet learning during the toddler years is likely to be much smoother: The child will have played an active role in his elimination process from an early age. He will associate toileting with the bathroom, and will likely become more curious and more eager to master this skill independently.

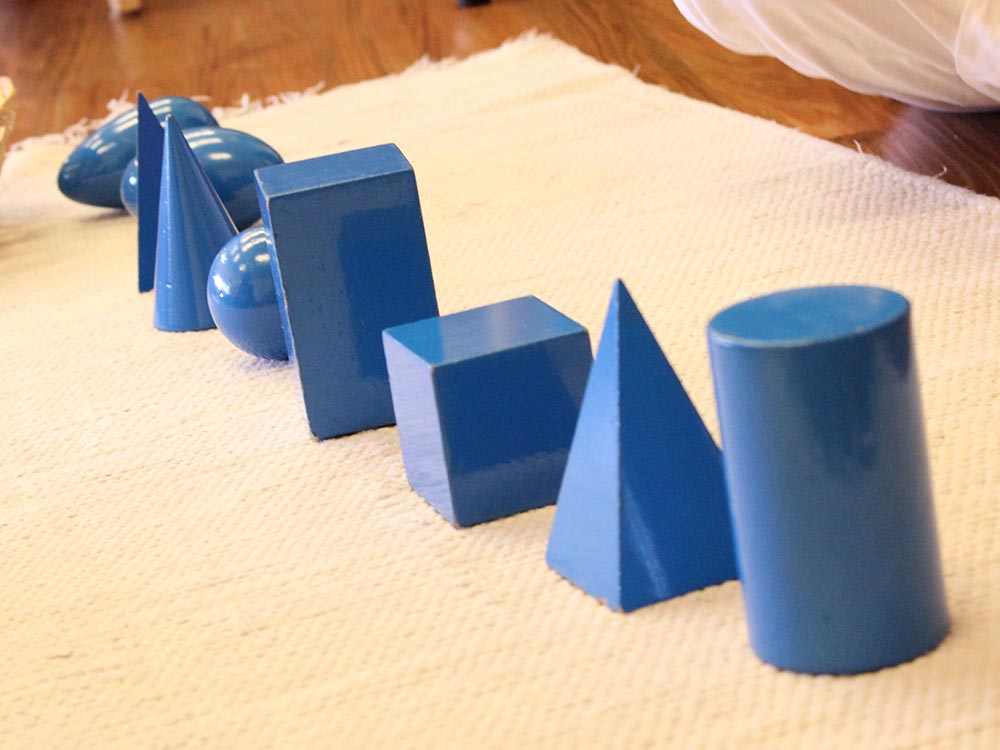

The movement area at first consists of a comfortable thin mat or a folded blanket placed on the floor. It is best if placed against a wall with a horizontal mirror along the side. Very young babies spend time here looking at simple mobiles created to develop the child’s visual sense. The mirror gives the child information about her body scheme (self-concept) and encourages movement, as children are very attracted by the image of themselves. As the child begins to get into a stable sitting position on her own, it is a good idea to place a low bar, such as a ballet bar, in front of the mirror to encourage pulling up to a standing position. This bar offers a sturdy support to practice standing and cruising. It’s much better at fostering gross motor skills than contraptions such as bouncers, saucers, and playpens, which often limit movement or provide unnecessary crutches. Your child’s conquest to develop his equilibrium will be met with confidence and a sense of empowerment if he is able to discover his amazing capabilities naturally at his own pace.

As your child begins to be mobile, the entire home will become the movement area! Let her explore. Movement is life and an essential basic need for the child. Children need to be able to safely move and explore their home environment. Take time to explore with her, creating areas that you know are entirely safe for exploration. One of my child’s favorite activities when he first started crawling was emptying the corner cupboard in the kitchen and crawling into it. The look of accomplishment on his face was well worth my effort to re-arrange the kitchen to make it a safe place for him to explore!

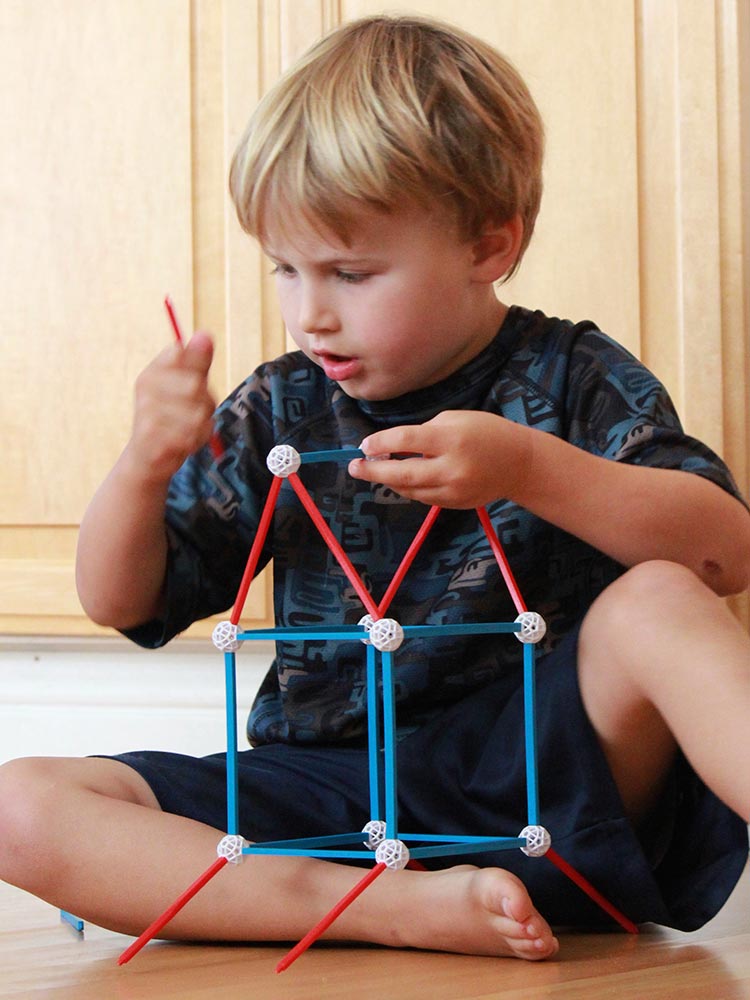

A child’s home should be simple and free of clutter. Less is truly more: a baby’s mind is still trying to find its way in the world, and too much stuff can be disorienting. For the movement and active area, use low shelves, with only a few toys, attractively displayed. (Extras can be stored away and swapped out.) The abundance of items can often overwhelm a child and get in the way of his need for concentration. Choose attractive and varied toys that are “passive”—that is, toys your child needs to engage actively with, rather than those that passively entertain without effort by the baby. Experience your home like your child sees it: crawl around and move things that you want your child to engage with at his level. This may mean lowering family photos and artwork so your child can admire them, and so they can be the springboard for engaging conversations and story telling.

The impact of adapting your home in this way is well worth the effort.

Not long ago I worked with a lovely single mother living with her eighteen-month-old son. The mom admitted it was hard to stay home with her son, since she felt she would “go crazy.” She would spend a large part of her day at the park with her son to avoid the common frustrations she experienced when he was at home for an extended period of time.

It did not take me long to see that the environment was not satisfying her son’s needs for independence, collaborative work and his need for order. The toy shelves were over-flowing with toys, the kitchen and bathroom had not yet been adapted for a young child and strangely enough the backyard was fenced off. I worked with this mother to make adaptations in her home—such as creating child-centered spaces in the kitchen, bathroom, and backyard by reducing the toys available down to a more manageable level. With these simple changes, my client was finally able to enjoy staying home with her son as she saw him being engaged, self-disciplined and able to concentrate on the developmentally appropriate activities set out for him. As she wrote to me,

“The changes in my son were immediate! Every new task and responsibilities I presented him with were so exciting to him. He thrived to help, participate and was eager to learn. He could play with one toy for long periods of time, was a lot more focused, calm and serene. Our house became his own playground and a place where he can now safely explore and take part of.”

A Montessori home environment may be devoid of many of the traditional items found on a baby registry—yet it is a rich, beautiful environment for children to explore. For ideas on how to get started in your home, download our “Montessori babies must-have” list.

Jeanne-Marie Paynel, M.Ed, holds AMI Montessori diplomas for ages birth through six. She is a Montessori Parent Liaison for LePort Montessori Schools and the founder of Voila Montessori, where she guides and empowers parents to create age-appropriate home environments for their children.

Jeanne-Marie Paynel, M.Ed, holds AMI Montessori diplomas for ages birth through six. She is a Montessori Parent Liaison for LePort Montessori Schools and the founder of Voila Montessori, where she guides and empowers parents to create age-appropriate home environments for their children.

.

The floor bed is maybe the most controversial of the Montessori infant suggestions. Parents often wonder, will my child roll off his floor bed, or crawl off and begin to play? Well, that’s certainly the case—but is that an argument against or for the floor bed? By rolling off onto a soft carpet, from the height of a few inches, a child learns to recognize boundaries with little risk. By having the freedom to get out of bed when no longer tired, a child feels empowered, rather than trapped. Think about it from a child’s perspective: wouldn’t such a bed allow a baby to discover something fantastic, namely, that he is in control, that he can get himself to sleep and get himself up again: “I am the master of my movements, I don’t need to stay in my container and cry until somebody rescues me, I can even go to bed when I am tired, no need for me to wait until my sleepy cues have been interpreted.”

The floor bed is maybe the most controversial of the Montessori infant suggestions. Parents often wonder, will my child roll off his floor bed, or crawl off and begin to play? Well, that’s certainly the case—but is that an argument against or for the floor bed? By rolling off onto a soft carpet, from the height of a few inches, a child learns to recognize boundaries with little risk. By having the freedom to get out of bed when no longer tired, a child feels empowered, rather than trapped. Think about it from a child’s perspective: wouldn’t such a bed allow a baby to discover something fantastic, namely, that he is in control, that he can get himself to sleep and get himself up again: “I am the master of my movements, I don’t need to stay in my container and cry until somebody rescues me, I can even go to bed when I am tired, no need for me to wait until my sleepy cues have been interpreted.” Jeanne-Marie Paynel, M.Ed, holds AMI Montessori diplomas for ages birth through six. She is a Montessori Parent Liaison for LePort Montessori Schools and the founder of

Jeanne-Marie Paynel, M.Ed, holds AMI Montessori diplomas for ages birth through six. She is a Montessori Parent Liaison for LePort Montessori Schools and the founder of

The one material rule. A child may have one and only one activity out at a time. He can take any material he has received a lesson on from a shelf and work with it in a clearly-defined work space, such as a small table or a rug rolled out on the floor. Once he is done, he needs to put the material back in its proper spot on the shelf, before he can move on to his next activity.

The one material rule. A child may have one and only one activity out at a time. He can take any material he has received a lesson on from a shelf and work with it in a clearly-defined work space, such as a small table or a rug rolled out on the floor. Once he is done, he needs to put the material back in its proper spot on the shelf, before he can move on to his next activity.

Clear rules, and a respect for each child’s right to work without being forced to surrender the materials, is a key factor in the peacefulness parents observe when visiting our Montessori classrooms. Yet this respect, this refusal to allow one child to interrupt another’s activity, has another, equally important purpose: protecting a child’s right to work enables him to meet his need for mental nourishment, and, in doing so, helps him become a more centered, better adjusted young person.

Clear rules, and a respect for each child’s right to work without being forced to surrender the materials, is a key factor in the peacefulness parents observe when visiting our Montessori classrooms. Yet this respect, this refusal to allow one child to interrupt another’s activity, has another, equally important purpose: protecting a child’s right to work enables him to meet his need for mental nourishment, and, in doing so, helps him become a more centered, better adjusted young person.

Be clear on your goal: do you want to encourage voluntary sharing (trading value for value), or do you want to compel children to surrender their toys on demand? Our suggestions in this blog post focus on fostering voluntary interactions to mutual benefit. We want to help children see each other benevolently, to treat one another with respect, and to respect the rights of each child to their things and personal space. If your goals are different, you’ll want to think about different rules than those we outline here.

Be clear on your goal: do you want to encourage voluntary sharing (trading value for value), or do you want to compel children to surrender their toys on demand? Our suggestions in this blog post focus on fostering voluntary interactions to mutual benefit. We want to help children see each other benevolently, to treat one another with respect, and to respect the rights of each child to their things and personal space. If your goals are different, you’ll want to think about different rules than those we outline here. For community toys, support taking long turns.

For community toys, support taking long turns. Protect your child’s rights when needed; otherwise,

Protect your child’s rights when needed; otherwise,  In my family, we have been playing by these rules since my daughter was not quite three, and my son, not quite one: my children have never been compelled to surrender their toys on demand—not at home, not at the playground and not at their Montessori school. Yet they are both very caring, kind, friendly children—children who are quite adept at reading social clues, who can (usually) wait their turn, who speak up for their needs, and who have good relationships with their classmates and strong friendships for their age. Last summer, when we were on an extended play date with my daughter and four other six-year-old girls, one of my daughter’s friends hadn’t brought her bike along. This girl was walking alone as the other four girls were riding along happily on their bikes. After a short while, my daughter—who knew I would never ask her to share her bike—noticed her friend’s sad face and realized the friend felt left out. She got off her bike, took of her helmet, and invited her friend to take a turn.

In my family, we have been playing by these rules since my daughter was not quite three, and my son, not quite one: my children have never been compelled to surrender their toys on demand—not at home, not at the playground and not at their Montessori school. Yet they are both very caring, kind, friendly children—children who are quite adept at reading social clues, who can (usually) wait their turn, who speak up for their needs, and who have good relationships with their classmates and strong friendships for their age. Last summer, when we were on an extended play date with my daughter and four other six-year-old girls, one of my daughter’s friends hadn’t brought her bike along. This girl was walking alone as the other four girls were riding along happily on their bikes. After a short while, my daughter—who knew I would never ask her to share her bike—noticed her friend’s sad face and realized the friend felt left out. She got off her bike, took of her helmet, and invited her friend to take a turn.

And yet, in the reverse situation, the same parents often don’t reinforce the “no taking” principle. Instead of protecting their child’s play, they encourage (and sometimes admonish) their child to give up the toy in question.

And yet, in the reverse situation, the same parents often don’t reinforce the “no taking” principle. Instead of protecting their child’s play, they encourage (and sometimes admonish) their child to give up the toy in question.

Watching your young child grow up so quickly can be bittersweet—one minute you’re celebrating his first steps and his first words, then you blink and—gasp!—your child is ready for his first day of school!

Watching your young child grow up so quickly can be bittersweet—one minute you’re celebrating his first steps and his first words, then you blink and—gasp!—your child is ready for his first day of school! Part-time students don’t derive the full benefit from the Montessori environment as they never really get settled down in a consistent routine. I once worked at a Montessori school where primary students were given the option of attending school part-time for just three days a week. After a while, I began to observe a great difference between the part-time students and the full-time students who came to school five days a week: The part-time students appeared to spend much of their time aimlessly wandering around the classroom, while the full-time students were actively engaged in lessons on the floor or at a table, working independently, working with a classmate, or working with a teacher.

Part-time students don’t derive the full benefit from the Montessori environment as they never really get settled down in a consistent routine. I once worked at a Montessori school where primary students were given the option of attending school part-time for just three days a week. After a while, I began to observe a great difference between the part-time students and the full-time students who came to school five days a week: The part-time students appeared to spend much of their time aimlessly wandering around the classroom, while the full-time students were actively engaged in lessons on the floor or at a table, working independently, working with a classmate, or working with a teacher. Young children thrive when their daily lives are full of consistent routines. They do best when they can predict what is going to happen next. This kind of consistency happens when a child goes to school for five consecutive days in a row each week versus attending school for only two or three days a week. It is hard for a child to figure out their routine when they go to school every other day or for just a few days in a row!

Young children thrive when their daily lives are full of consistent routines. They do best when they can predict what is going to happen next. This kind of consistency happens when a child goes to school for five consecutive days in a row each week versus attending school for only two or three days a week. It is hard for a child to figure out their routine when they go to school every other day or for just a few days in a row! Part-time students feel left out of the full-timers close classroom communities. The part-time students in my class also appeared to be less likely to have strong bonds with their classmates. Why? They were missing out on important events or lessons that were given on the days they were off. Their full-time peers tended to gravitate toward other children who were there each day, children they could rely on to be there to play and work with. Disconnected from the rhythm of the classroom, and implicitly perceived as being less reliable (because often absent) playmates, the part-timers sadly lived at the edges of our solid classroom community—despite my best efforts to integrate them anew each week.

Part-time students feel left out of the full-timers close classroom communities. The part-time students in my class also appeared to be less likely to have strong bonds with their classmates. Why? They were missing out on important events or lessons that were given on the days they were off. Their full-time peers tended to gravitate toward other children who were there each day, children they could rely on to be there to play and work with. Disconnected from the rhythm of the classroom, and implicitly perceived as being less reliable (because often absent) playmates, the part-timers sadly lived at the edges of our solid classroom community—despite my best efforts to integrate them anew each week. When you enroll with your child in LePort’s Toddler Parent & Child class, you enter a beautiful room where everything has a place and a purpose. It’s an environment carefully prepared to enable toddlers to fulfill their urgent need to act independently and to explore with all their senses. Everything is at the child’s level, on wooden furniture sized just right for toddlers. Your child will be excited to take the many interesting materials from the shelves and explore them with you. Parent & Child classes are held in the same Montessori toddler environments that our 18 to 36 month old students enjoy in our drop-off Montessori programs.

When you enroll with your child in LePort’s Toddler Parent & Child class, you enter a beautiful room where everything has a place and a purpose. It’s an environment carefully prepared to enable toddlers to fulfill their urgent need to act independently and to explore with all their senses. Everything is at the child’s level, on wooden furniture sized just right for toddlers. Your child will be excited to take the many interesting materials from the shelves and explore them with you. Parent & Child classes are held in the same Montessori toddler environments that our 18 to 36 month old students enjoy in our drop-off Montessori programs.

Some parents who discover Montessori when their child is four years old are concerned about joining the mixed-age primary room mid-stream. “Will my child be playing catch-up? Some of the other four-year-olds are already reading ”, you might wonder. “I’ve just learned about Montessori, and I see how wonderful this environment could be for my child. She’s already four, though. Did we miss the boat?”

Some parents who discover Montessori when their child is four years old are concerned about joining the mixed-age primary room mid-stream. “Will my child be playing catch-up? Some of the other four-year-olds are already reading ”, you might wonder. “I’ve just learned about Montessori, and I see how wonderful this environment could be for my child. She’s already four, though. Did we miss the boat?” It is true that younger is better when it comes to joining a Montessori program. Starting as a toddler or a young three-year-old gives children the best opportunity to benefit from the enriched, carefully prepared classroom environment. As Montessori educators, we understand that the time between birth and age six is the most critical in a human being’s development. During this stage of growth, children go through rapid changes and develop the most important aspects of their personality and intellect.

It is true that younger is better when it comes to joining a Montessori program. Starting as a toddler or a young three-year-old gives children the best opportunity to benefit from the enriched, carefully prepared classroom environment. As Montessori educators, we understand that the time between birth and age six is the most critical in a human being’s development. During this stage of growth, children go through rapid changes and develop the most important aspects of their personality and intellect. While some of these sensitive periods begin at birth, four-year-old children are still in the midst of this amazing time. We regularly see four-year-olds join our class and become drawn to the materials on our shelves; they quickly begin “working” and become acclimated to their new environment. With the right support at home and at school, you’ll be surprised by how much joy both you and your child will get from his Montessori experience!

While some of these sensitive periods begin at birth, four-year-old children are still in the midst of this amazing time. We regularly see four-year-olds join our class and become drawn to the materials on our shelves; they quickly begin “working” and become acclimated to their new environment. With the right support at home and at school, you’ll be surprised by how much joy both you and your child will get from his Montessori experience! This consistent time is especially important for your four-year-old who is new to Montessori. Dr. Montessori observed that many issues that children struggle with, from temper tantrums to uncoordinated movement, from disobedience to physical aggression, disappeared when children are allowed freedom in an environment suited to their needs. Often, a child would find some activity that spoke to him, become immersed in it, and repeat it over and over again. Once a child connected to an engaging activity, he became happier, more curious to explore more learning materials in class, and even became kinder and more benevolent to his peers.

This consistent time is especially important for your four-year-old who is new to Montessori. Dr. Montessori observed that many issues that children struggle with, from temper tantrums to uncoordinated movement, from disobedience to physical aggression, disappeared when children are allowed freedom in an environment suited to their needs. Often, a child would find some activity that spoke to him, become immersed in it, and repeat it over and over again. Once a child connected to an engaging activity, he became happier, more curious to explore more learning materials in class, and even became kinder and more benevolent to his peers. The third year in Montessori Primary (the equivalent of traditional kindergarten) is the year when much of the foundational skill development solidifies, and many children suddenly experience huge growth spurts in writing, reading, math and overall confidence.

The third year in Montessori Primary (the equivalent of traditional kindergarten) is the year when much of the foundational skill development solidifies, and many children suddenly experience huge growth spurts in writing, reading, math and overall confidence. The best way to help your child thrive in a Montessori environment is to better understand Montessori yourself. We make this easy for you: When your child joins our program, you’ll receive eight short, one-page handouts explaining key aspects of Montessori, and suggesting simple ways you can align what you do at home with what your child experiences at school. Throughout the school year, we offer Parent Education Events, where we discuss a wide range of topics: from how to support independence to learning math in preschool. Our blog also offers plenty of helpful articles. Your child’s teacher is also a great resource: Our trained head teachers are available via email or in person after school to answer all kinds of Montessori-related questions you may have and to help you understand how you can best support your child.

The best way to help your child thrive in a Montessori environment is to better understand Montessori yourself. We make this easy for you: When your child joins our program, you’ll receive eight short, one-page handouts explaining key aspects of Montessori, and suggesting simple ways you can align what you do at home with what your child experiences at school. Throughout the school year, we offer Parent Education Events, where we discuss a wide range of topics: from how to support independence to learning math in preschool. Our blog also offers plenty of helpful articles. Your child’s teacher is also a great resource: Our trained head teachers are available via email or in person after school to answer all kinds of Montessori-related questions you may have and to help you understand how you can best support your child. One of the beauties of Montessori is the profound respect for the individuality we give each child. Montessori teachers do not compare their students with each other. We know that your four-year-old may need some time to get used to his new school, and that it would not help at all to compare him to other four-year-olds who had started before him. Each Montessori teacher allows her students to develop at their own pace, and she trusts that the Montessori classroom will enable her students to reach their individual potential at their own unique pace.

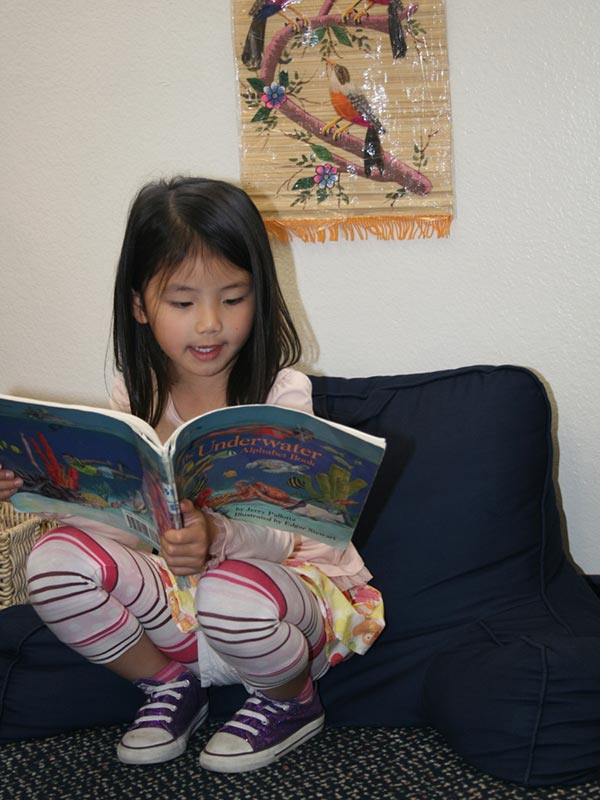

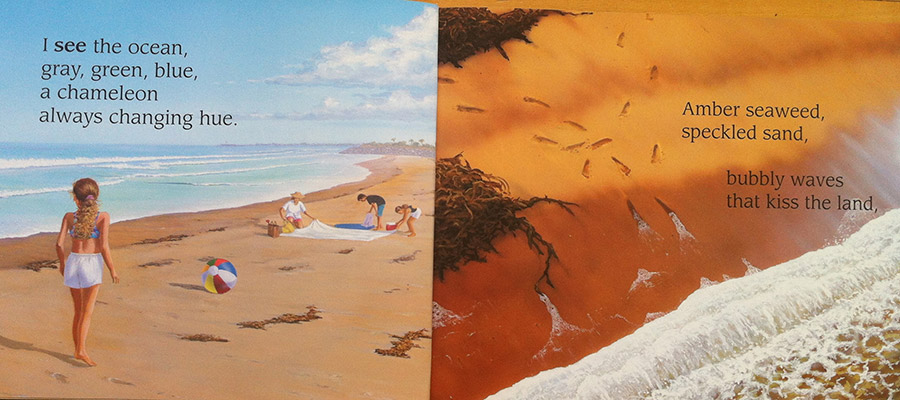

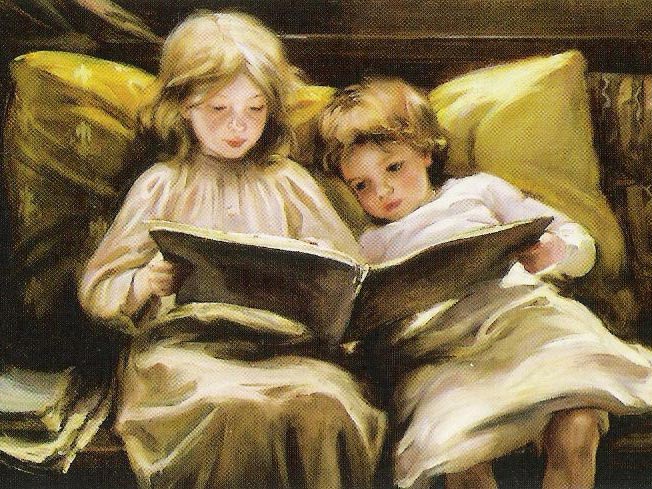

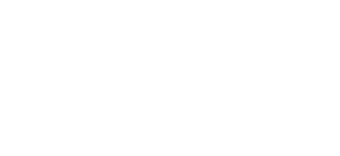

One of the beauties of Montessori is the profound respect for the individuality we give each child. Montessori teachers do not compare their students with each other. We know that your four-year-old may need some time to get used to his new school, and that it would not help at all to compare him to other four-year-olds who had started before him. Each Montessori teacher allows her students to develop at their own pace, and she trusts that the Montessori classroom will enable her students to reach their individual potential at their own unique pace. If you want to support your child’s academic development, the best way to do this is to read with your child. Read a lot! Read a variety of books, discuss what you read, ask her questions about what you’ve read, follow along with your finger under text as you read, and explain vocabulary. That way, when she does finally master her letter sounds, she’ll be able to move along much faster. Find suggestions for

If you want to support your child’s academic development, the best way to do this is to read with your child. Read a lot! Read a variety of books, discuss what you read, ask her questions about what you’ve read, follow along with your finger under text as you read, and explain vocabulary. That way, when she does finally master her letter sounds, she’ll be able to move along much faster. Find suggestions for