Starting preschool in a foreign language: How the Montessori environment helps children transition when they don’t speak the classroom language.

Every year in our toddler and preschool rooms, we welcome children who do not speak the classroom language. Mostly, we’ve welcomed non-English speakers into our English-language rooms. Now, with our new Spanish and Mandarin immersion programs, we are also helping English-speakers to transition into classrooms with a new language for them—a very similar transition, as both teachers speak only Spanish/Mandarin, all day long!

Parents often ask how children who do not speak the classroom language handle the transition. After all, it’s already a new environment—and now they need to enter it without understanding the language the teachers and many of their peers speak!

To help you address these concerns for your child, this blog post discusses how the Montessori environment is optimally set up to support the learning of a second language, how we help children transition, and what you, as the parent, can do to help your child make a successful start in his new environment.

How the Montessori environment supports learning a new language

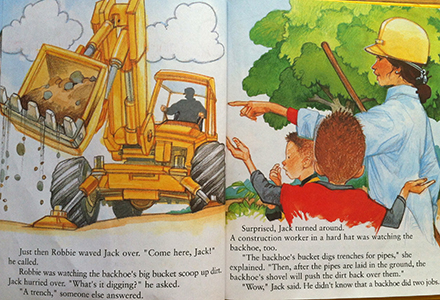

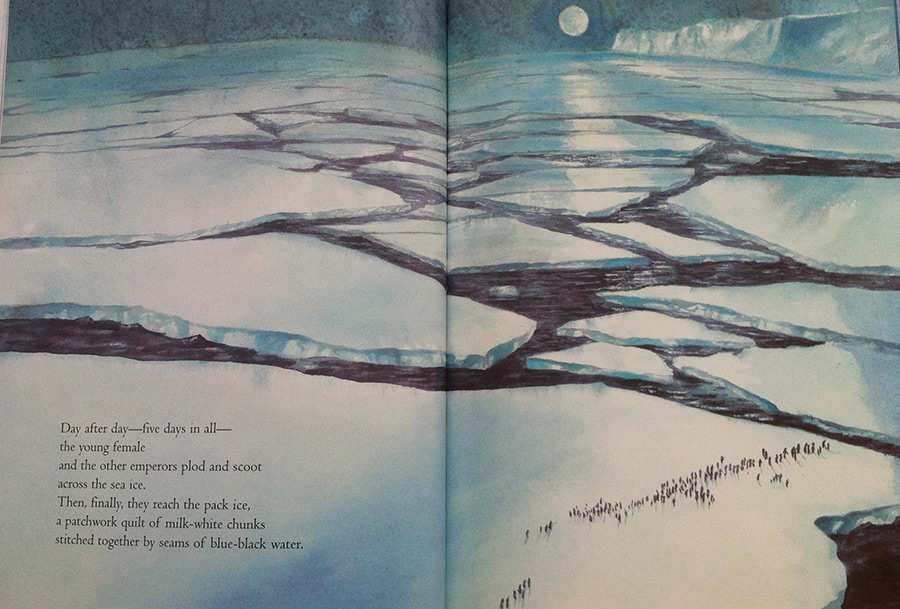

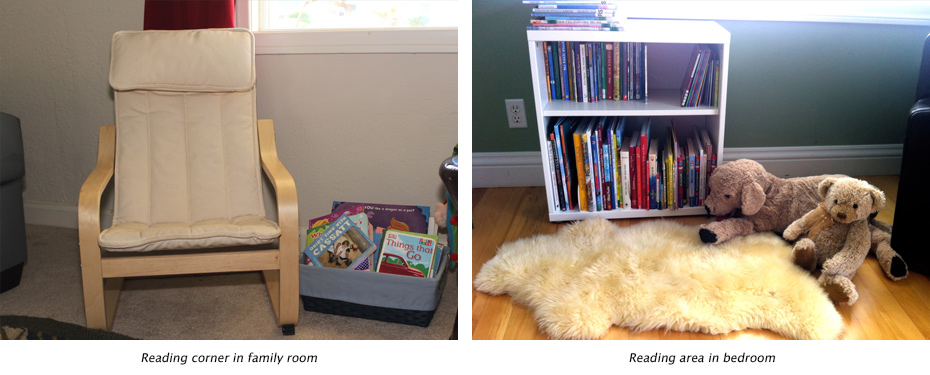

- An environment that is largely accessible without language. The Montessori classroom is a very hands-on environment. Most materials are readily usable without any language skills: children can take a puzzle, blocks or play dough, and enjoy themselves even if they cannot speak the language. There are few all-group, language-heavy activities. What group activities there are—read-aloud, song time, small-group lessons—tend to be voluntary, so that a child who doesn’t have the language skills (or just isn’t interested!) has the option of doing something else.

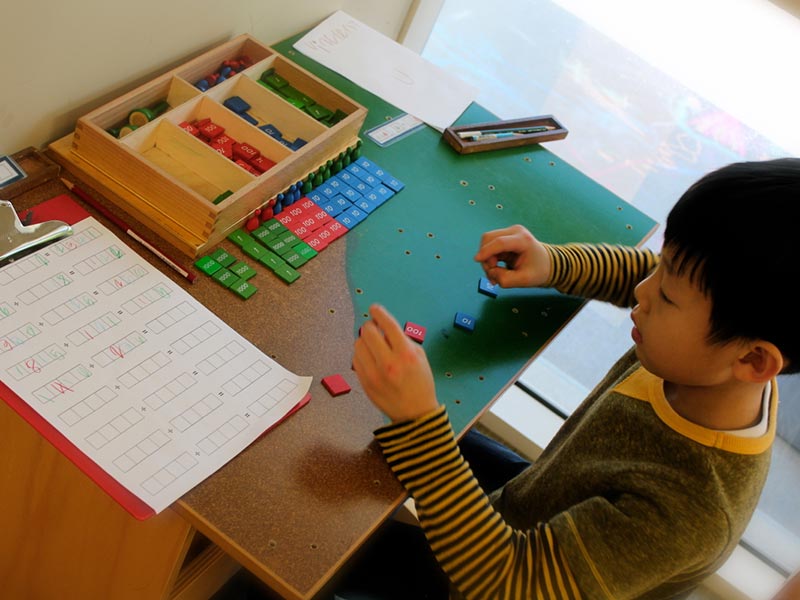

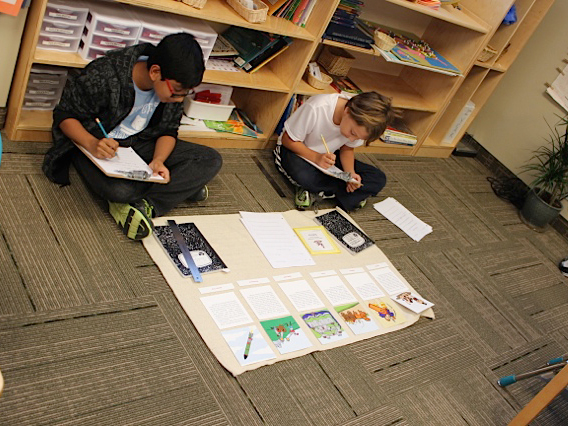

- Individual demonstrations, with materials, not purely verbal lessons. In Montessori for toddlers and preschoolers, most of the instruction is one-on-one. A child sits down with a teacher who demonstrates, in slow, careful movement, how a certain activity works. The child can follow along and learn how to do it, even if he initially doesn’t understand the words the teacher offers.

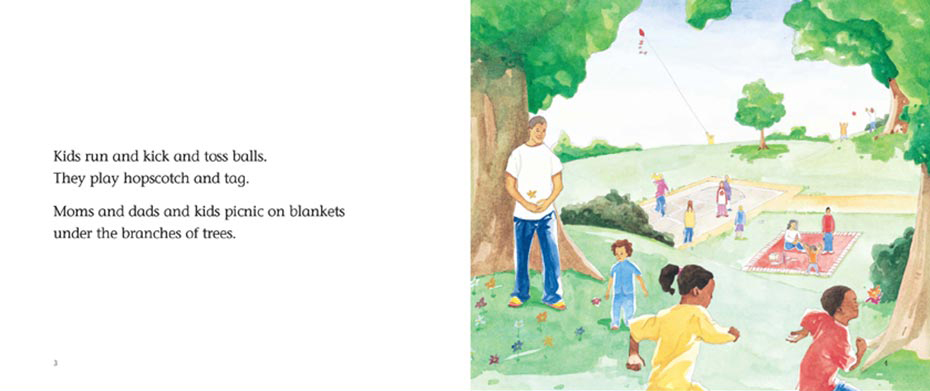

- A multitude of materials and experiences to support language acquisition in response to a child’s interests. Research has shown that language learning happens optimally when the words provided tie to an activity in which the child is engaged. In his Montessori classroom, your child will work with a wide range of activities, which enable the teachers to provide never-ending responsive language. Here are just a few examples:

- Practical Life activities lend themselves for teaching the names of common things, as well as lots of verbs and adverbs. A teacher may show your child how to paint at an easel. There are all the words for the material in use (easel, brush, color, water cup, apron, sponge and so on); all the words for the activity (hang up the paper, paint, clean, dry); and, of course, the words to describe the end product (clear, colorful, bright).

- Sensorial materials are great for teaching adjectives of all kinds. Many activities in the sensorial area are designed to isolate a certain attribute—the sound something makes (loud, quiet, high tone/low tone), the color (dark blue, light pink), the texture (coarse, fine, soft, hard), the smell, the taste, the shape, the size, and so on. All of these are wonderful activities for teaching language skills!

- Grace and Courtesy lessons help the child learn to express his needs and feelings with words. A key skill all children need to learn—even in their native language—is to use words to communicate needs and emotions. We actively model respectful, kind interactions: “May I please have this block back? Jack is working with it!” We describe what we see, calling children’s attention to the emotions of others: “Sam’s face shows me he is sad. See the tears in his eyes? See his eyebrows: they’re in a frown!”

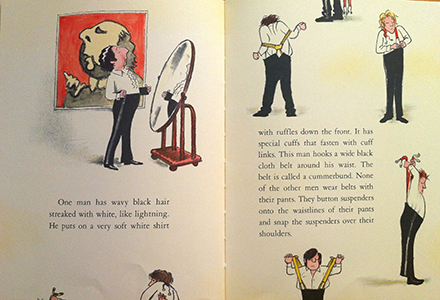

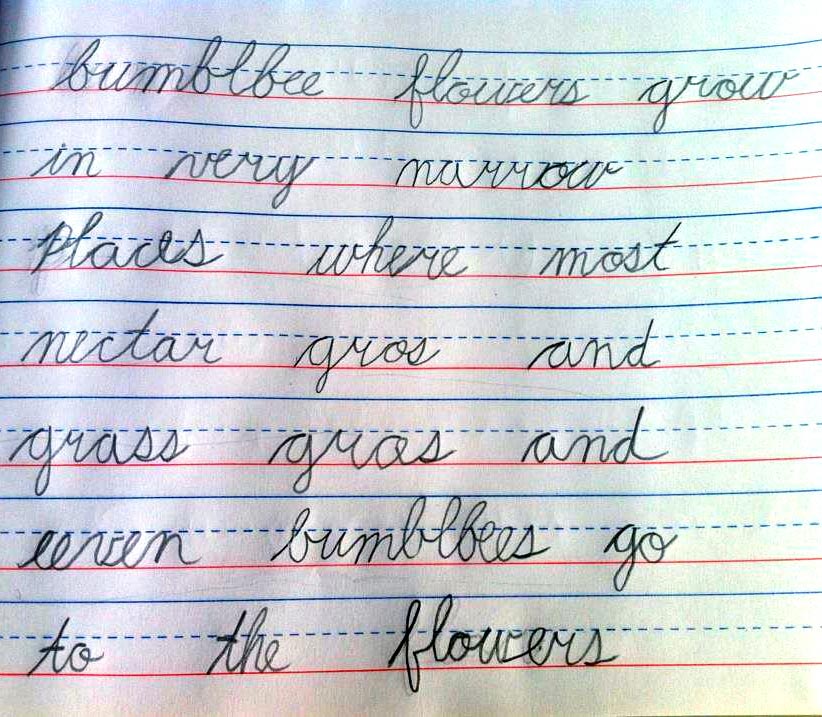

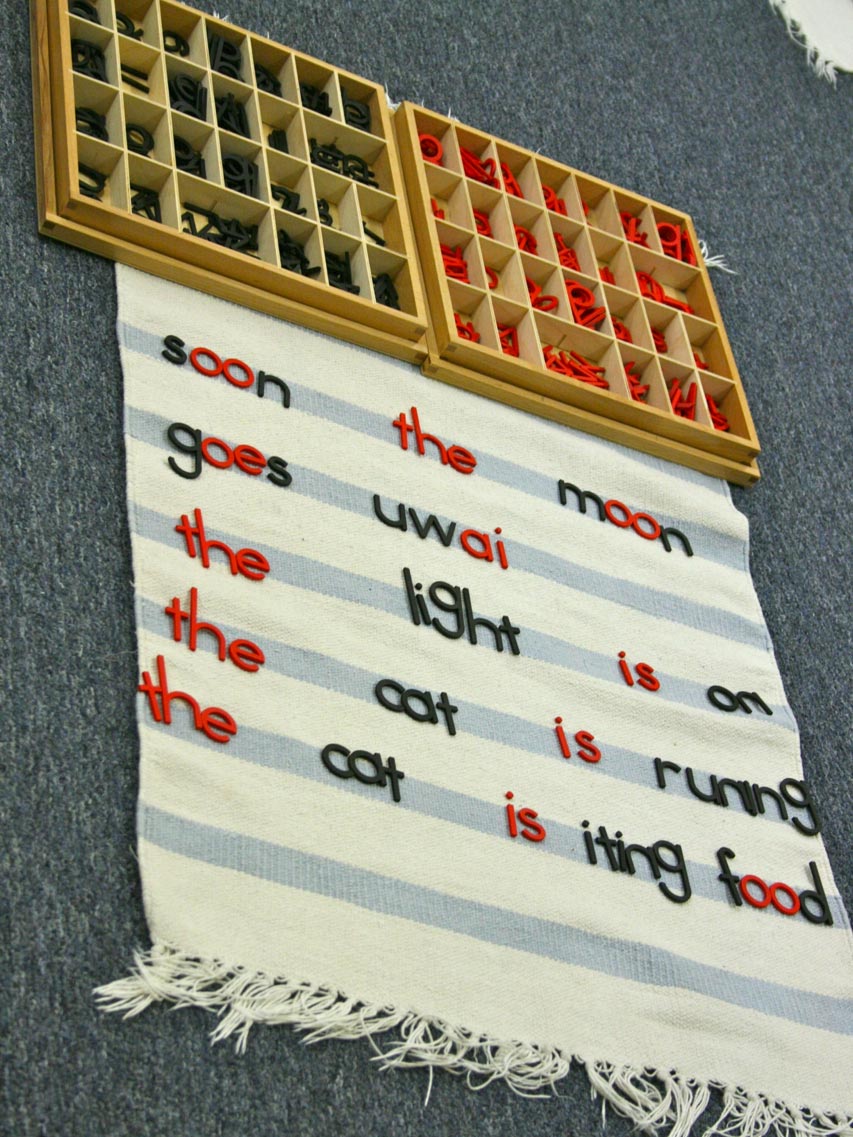

- An explicit language curriculum. Montessori guides are experts at giving children new words. We use a very simple but effective approach called the Three Period Lesson:

- Naming Period: “This is a cow.” The teacher may show an object, or a picture, and provide the child with the name, then pause to allow the child to repeat the name.

- Recognition and Association: “Point to the cow.” To check the child’s understanding, the teacher will play a game of asking for an object or a picture, guiding the child to hand it to her, put it at the edge of the table, back in the basket, and so on.

- Recall: “What is this?” Only after the child has shown he can identify the object, does the teacher ask her to name it un-aided.

This Three Period Lesson gets used all over the classroom: we have many language cards with common objects, such as things from around the house to clothing, from vehicles to animals and so on. We also use this approach to, later, teach more advanced concepts—such as the names of countries, the parts of animals, or types of rocks.

- A clear, repetitive structure to support independence. Consistency and predictability are a great help to a child who enters any new setting. This is especially true when a child enters a classroom without speaking its language. Our Montessori toddler and preschool rooms combine freedom for individual activities with a very clear structure and routine. Children learn that they can choose any activity from the shelves, and work with it for as long as they want. They learn that the teacher rings a bell when it is clean-up time, and that they may either put their activity away, or, for older children, mark them as theirs to come back to after lunch.

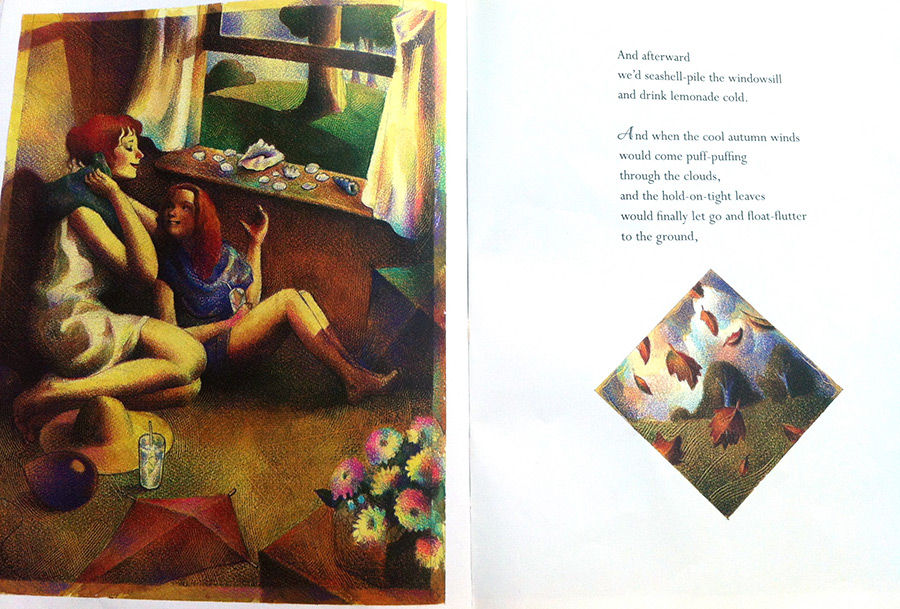

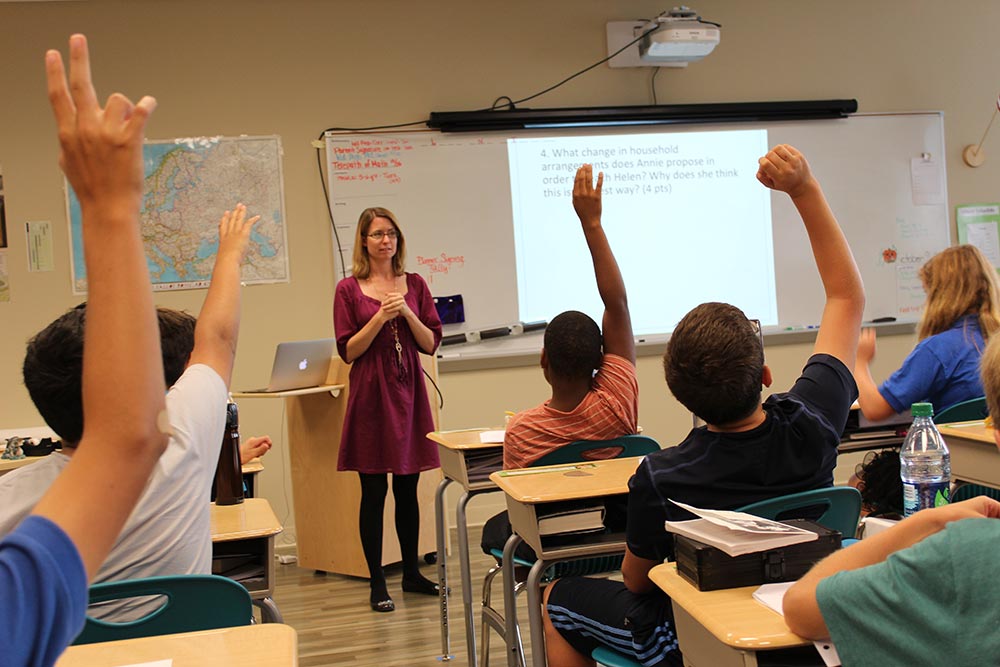

- An ability to observe and learn from peer modeling. Much learning in our classroom happens when children observe other children do activities. A child who joins at age three without language skills can watch as another child builds the Pink Tower, or punches out the shape of a continent, or uses scissors to cut along lines. She can see how children return activities to the shelf, how they clean an easel after using it, or how they sit down at the snack table when a spot is free. Because much of the learning happens at a perceptual, non-verbal level, even children who do not speak the language can easily model after others.

- A community where older children are eager to help. Our Montessori classrooms are mixed-age, family-like environments. Just like younger children in a family learn much language from the older children, younger students who enter a Montessori environment learn much language from their older peers. Older students often naturally act as translators for younger peers who speak their language!

- A focus on polite, gracious interactions between children. Some parents fear that children who do not speak the language may suffer socially. We don’t see that happening in our classrooms! Instead, our students all receive lessons in “Grace and Courtesy”: they learn how to greet a child, how to offer help, how to express their feelings and needs using words. As a result, our students tend to be quite empathetic, and willing to help a new child find her way around class.

Special support for those new to the classroom language

- Teachers add gestures and hand signals to spoken language. Our teachers are experts at using gestures and body movements to help children understand them and, in short order, learn to recognize key words and phrases in their new language. We may point to a jacket and pantomime taking it off. We may pull out a chair and point to the child, then the chair, to show the child where to sit down. We may point to the toilet to suggest it’s time for a child to use it. Basically, we do what you did when your child first learned to speak: we slow down, we point, we repeat—so your child can learn his second language by absorbing it from his surroundings, just like he did with his first.

- Pairing up of new students with language-skilled peers. Since we have mixed-age classrooms, we are often able to pair a new child with an older child who speaks her language. This is especially true in places like Irvine, where we have a many children who come to us speaking Chinese, Korean or Japanese. Feel free to ask your Head of School if there are classrooms with other children who speak your native language; while we can’t guarantee a match-up all the time, we will do our best to accommodate your child’s language needs. (In our immersion classrooms, we may pair-up English-speaking students with those who already know Mandarin or Spanish.)

- Frequent updates and check-ins with parents. While we encourage all parents of new students to check in with us regularly, we place a special emphasis on frequent updates for those children who come to us without speaking English. Please do share any concerns you have, and help us by letting us know any needs your child may have that he cannot yet reliably communicate in English or the immersion language.

What parents can do to help

- Explain school routines to your child. Before your child starts, review the flow of the school day with him. You can also access your campus’ photo gallery, and use the photos as prompts to talk about school with your child. Feel free to ask your teacher or Head of School for a detailed schedule of your child’s classroom, so you can share all the details with her. Finally, it will be helpful if you can explain a few basic classroom rules to your child before she starts—such as having only one activity out at a time, putting it back on the shelves when done, and not stepping on the rugs children place on the floor to delineate work areas. We can help you with explaining these rules when you come in for your Meet and Greet with your child’s teacher.

- Teach your child a few key words in English. It’s very helpful if your child comes to school knowing a few key words in English to make his needs known. Some words to consider teaching: (I’m) hungry, thirsty, tired, hurt; pee, poop; (I need) help, water, food, bathroom. (We don’t need children to learn these words in Spanish or Mandarin Chinese in our immersion classrooms, as our immersion teachers speak English in addition to Spanish or Chinese.)

- Provide the teacher with a few words in your language. We’d love it if you provided us with the same list of words in your language, so we could better meet your child’s needs during the initial transition.

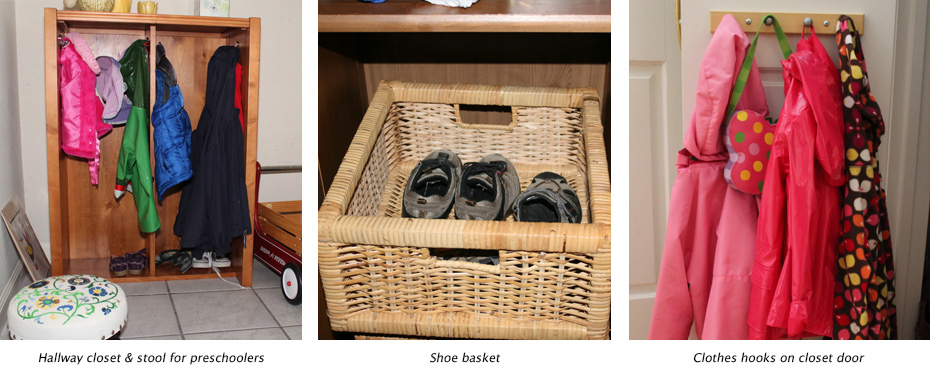

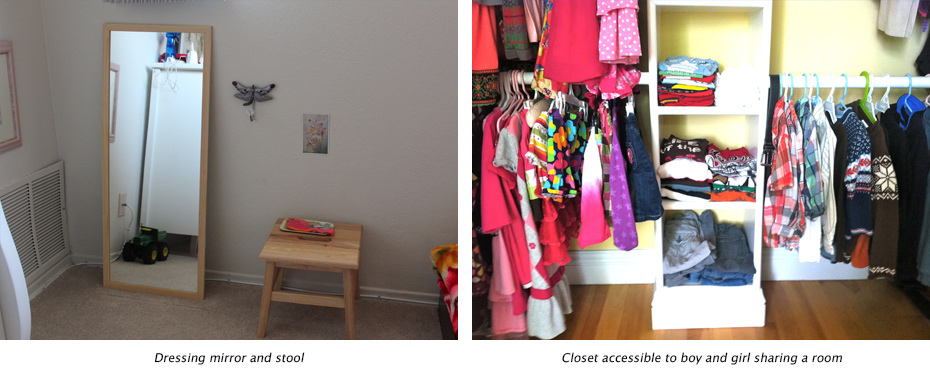

- Help your child toward independence (especially if he’s three and above). Our Montessori curriculum places a strong emphasis on helping children become functionally independent—on learning to dress themselves, eating by themselves, using the toilet independently, completing a work cycle on their own. If you, a relative or a nanny have been helping your child with many of these everyday tasks, you can help with the transition to school by slowly introducing more independence at home as well. This article offers some good ideas on how to get started.

One more thing: if you speak a language other than English at home, and are enrolling your child in one of our English-speaking classrooms, we’d encourage you to continue speaking your native language at home. Living in America, and being in an English-speaking setting all day long, your child will learn English well—so well that, unless you consistently speak your native language at home, it will disappear from his life. Growing up bilingual is such a gift, it’s worth the hard work that goes into making it happen!