Selecting Read-Aloud Books, the Montessori Way

Part three of four of our reading aloud blog post series

Great books are essential if reading with your child is to be a joyful, replenishing experience, a highlight of the day.

When I first set out to find books for my two children, I quickly discovered that choosing outstanding children’s books is a challenging task. Our local library has an extensive picture book collection. I headed there, and asked a few of the librarians for advice. One handed me a somewhat helpful trifold booklet of 25 favorite books; another one suggested some well-known classics (The Hungry Caterpillar, Goodnight Moon, The Big Red Barn.) It was a start, but few of the books really got me excited, and much of what was suggested just didn’t seem right for my vision of reading.

Over the past five years, as my children have grown older, I’ve discovered many good resources, approached Montessori-inspired friend and LePort teachers for ideas, and built a library for our family that we treasure, filled with picture books all of us love to re-read many times, along with an ever-growing list of books we put on hold and pick up at the library.

If you want some guidance on selecting books that are in line with your child’s Montessori education, books that you might enjoy reading as well, here are some principles to keep in mind on your library trips:

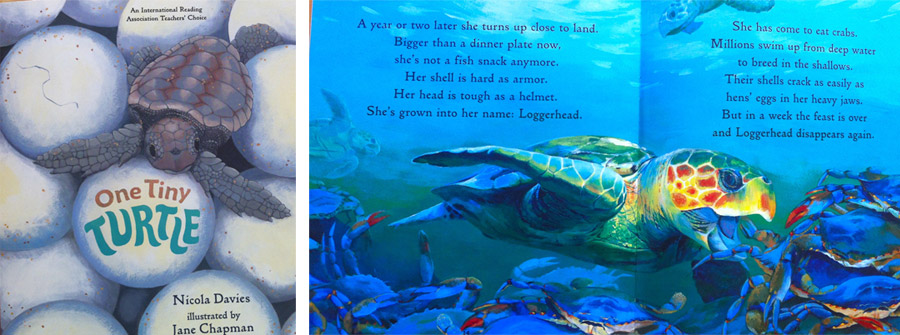

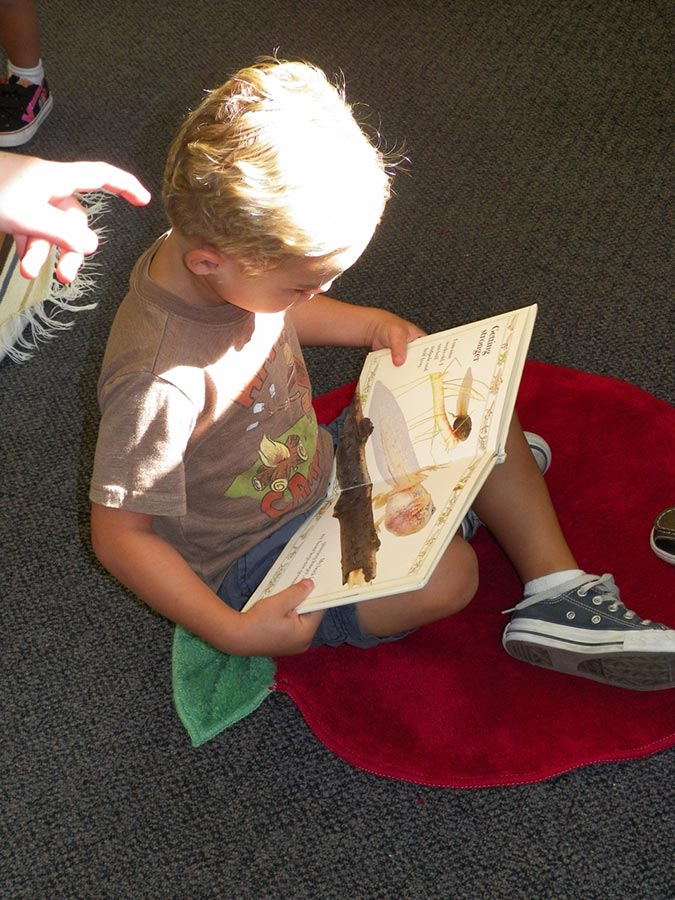

- Find books that “are real or could be real” for your younger reader. To a toddler or young preschool child, the real world is full of mysteries. A three-year old is fascinated by how different animals live, how things work, what the world looks like, why people act the way they do. Because young children do not yet have a clear conception of the difference between reality and fantasy, they are best served by books that either are about real things (non-fiction books) or stories that could be real (events that could actually happen, even if they are fictional). So when you select books for children younger than 5 or 6 years old, make sure you pick a preponderance of books about the real world. If you choose to share some occasional fantastic stories (of which there are some great ones, e.g. of the type that includes talking, anthropomorphized animals), make sure you help your child to understand what is real, and what is just pretend. (“Do animals talk? No, they don’t: this book is a fantasy book.”)

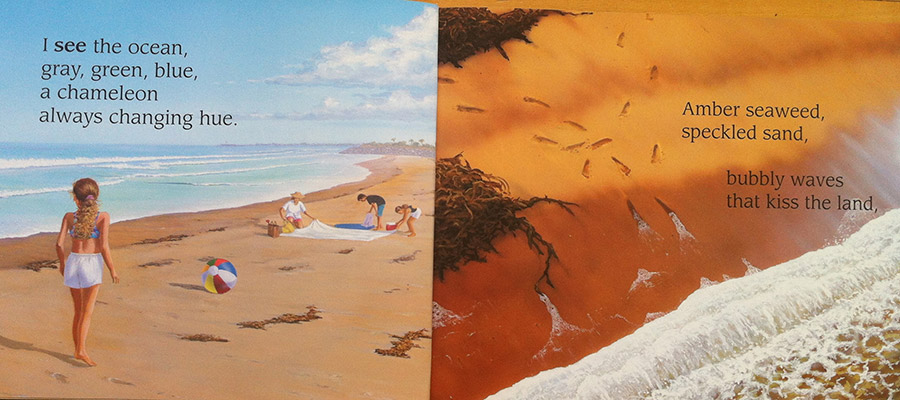

- Read up to your child, not down. Toddlers and preschoolers are in what Montessori calls the sensitive period for language: like little sponges, they absorb effortlessly the language around them. Preschool children can readily learn big vocabulary words, when the words are introduced in an accessible way. By selecting books with appealing and appropriately complex language models, you greatly aid your child’s language acquisition. Many children’s books unfortunately use very short, choppy language, and are overly simplistic. My rule of thumb is to buy up, not down: I’ve always picked books that had bigger words, longer sentences, more elaborate constructions, than most people would think appropriate for a 2- or 4-year old. In most cases, my children were engaged—and I was surprised and delighted to hear them pick up and use the language of the books. (“East sky purples, sun is coming”, my then 3-year-old daughter echoed after Bats on the Beach. “Mama, we don’t need to dread this knight: he’s extinct, like the dinosaurs”, explained my 3-year-old son as we read Cowardly Clyde.)

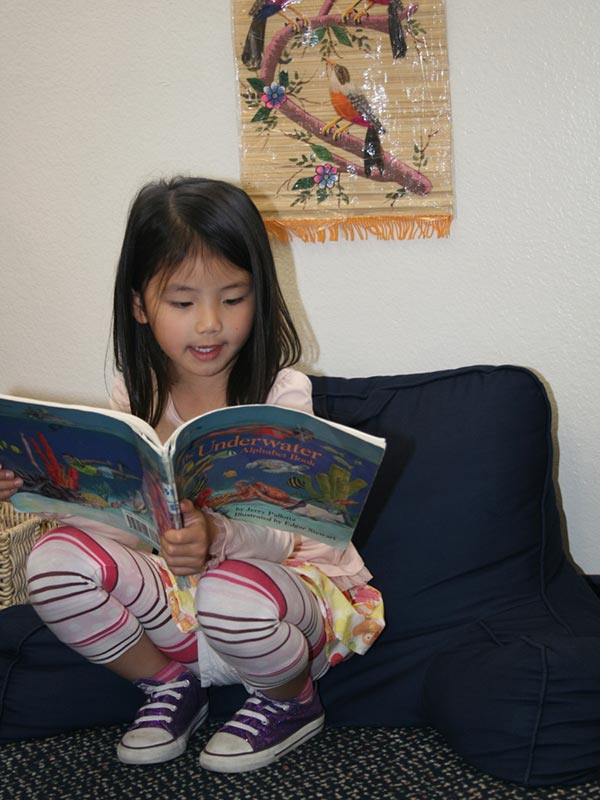

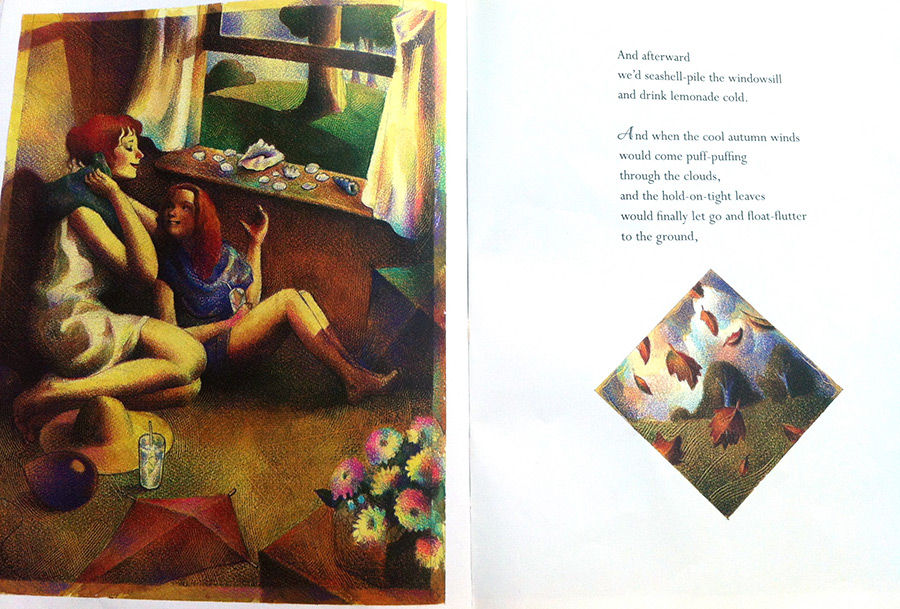

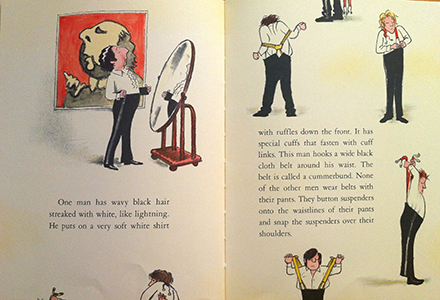

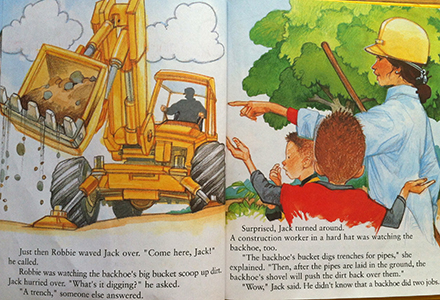

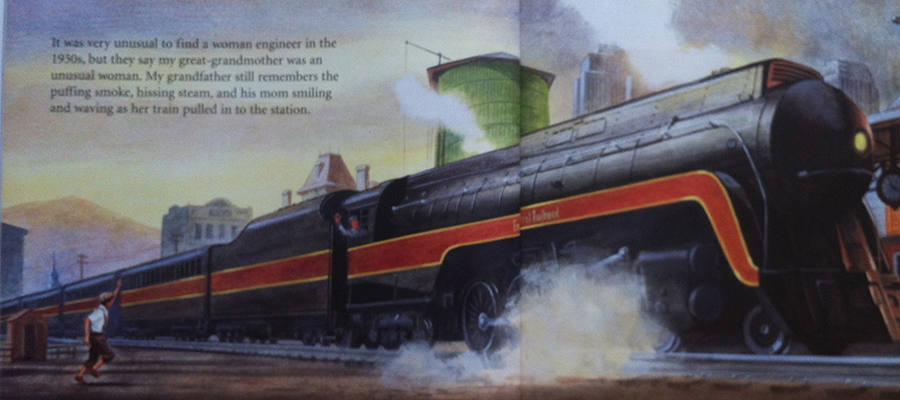

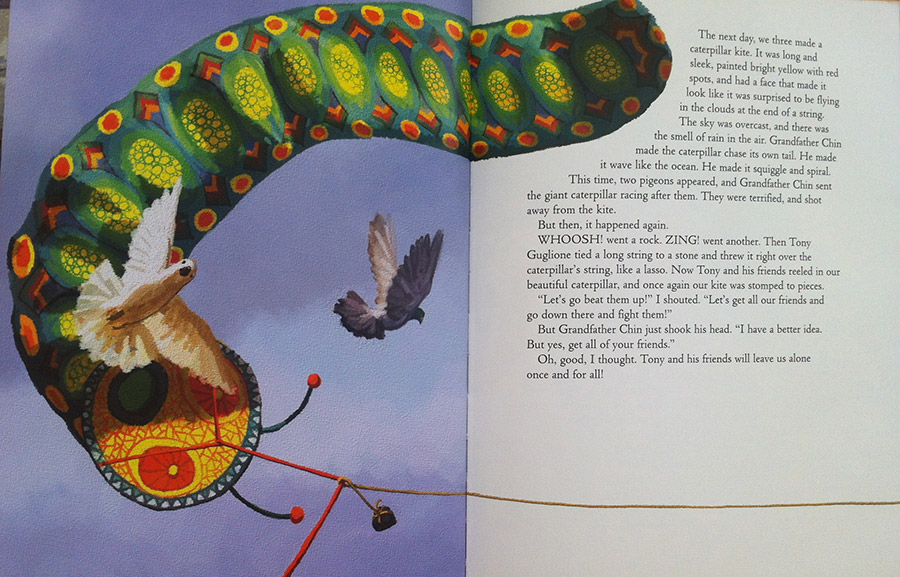

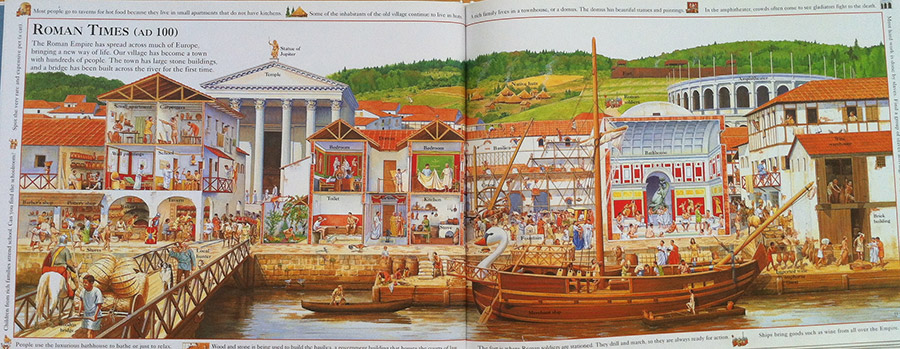

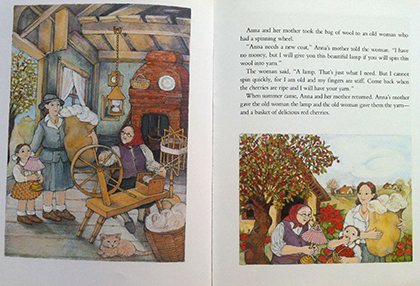

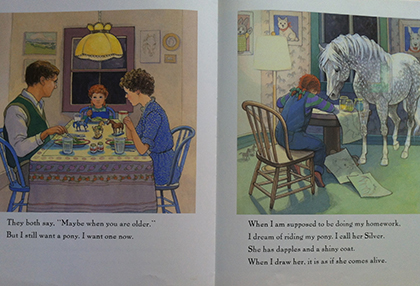

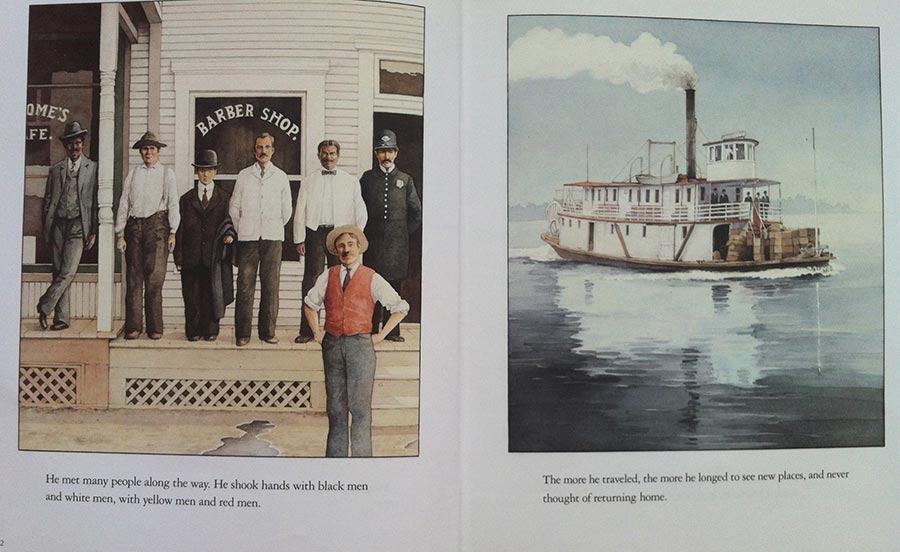

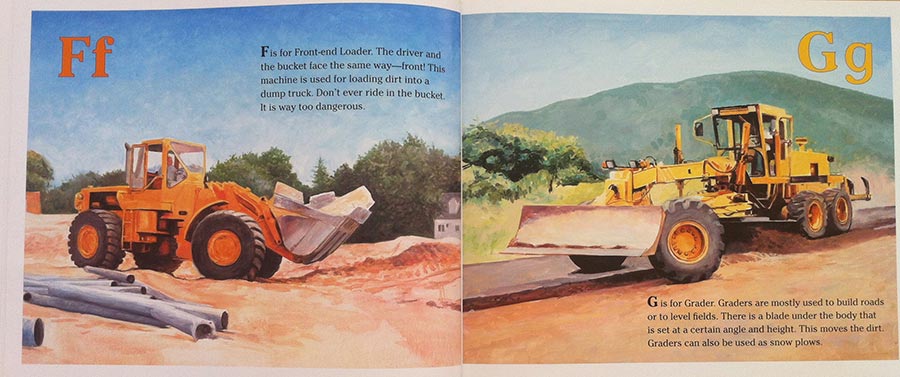

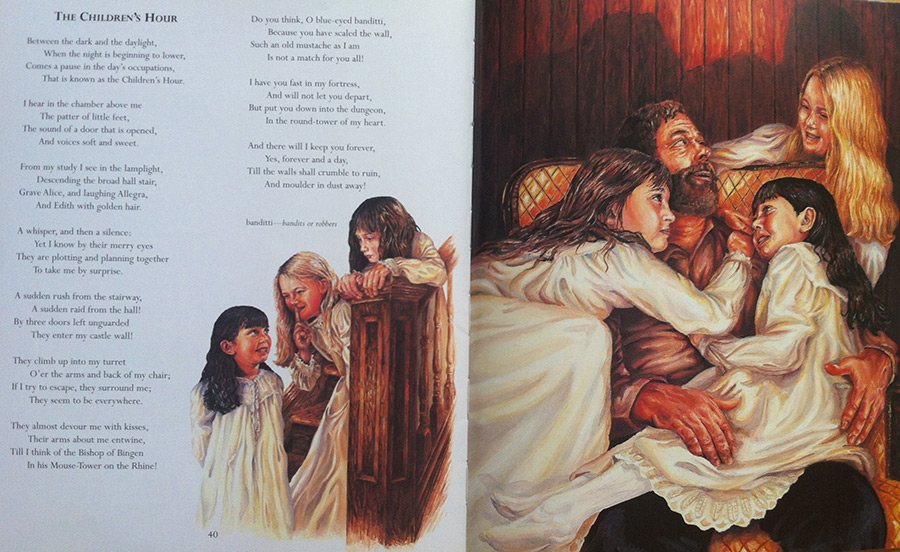

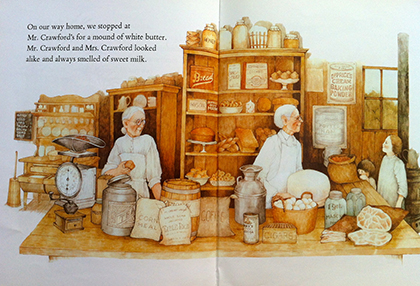

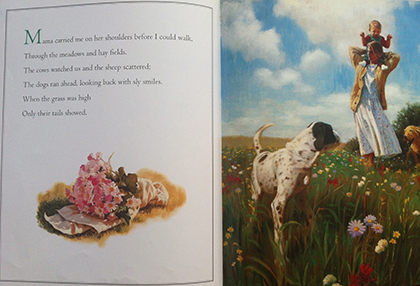

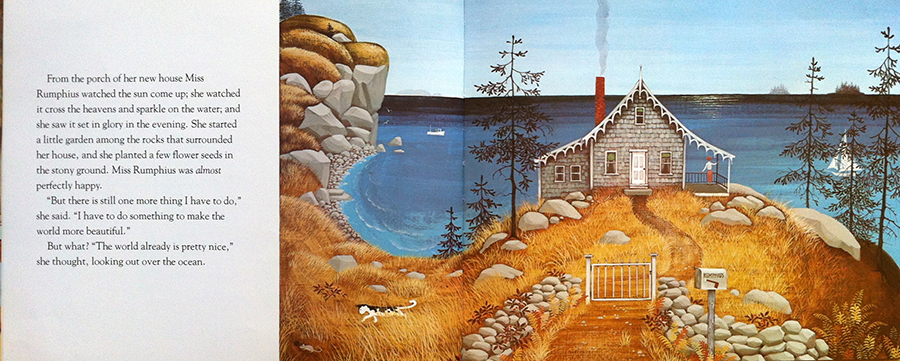

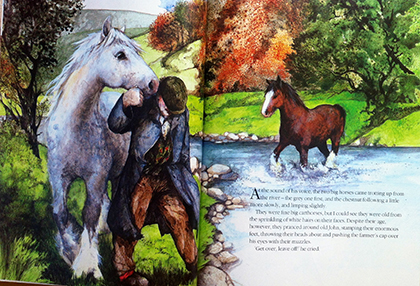

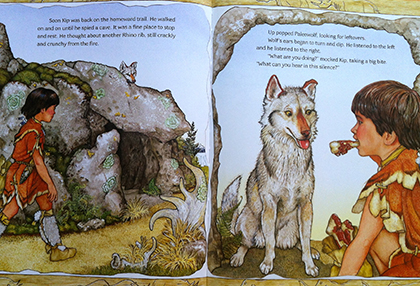

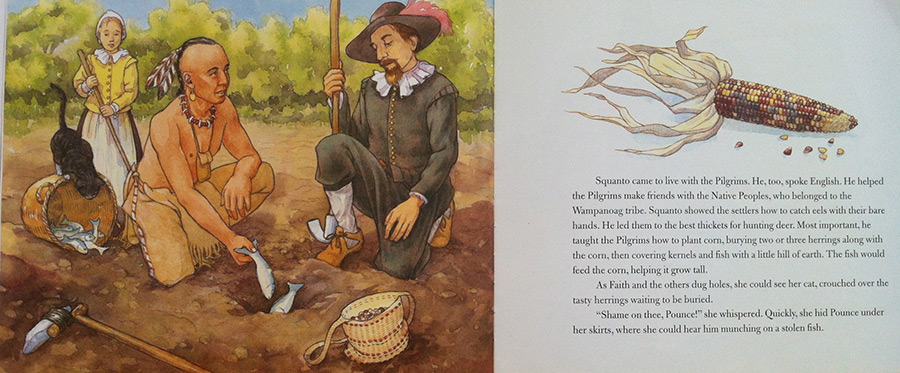

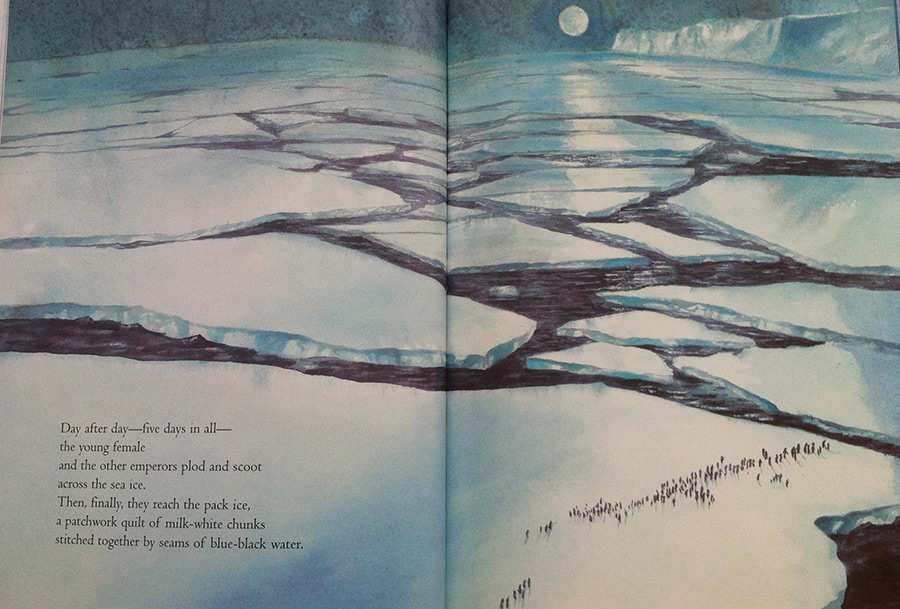

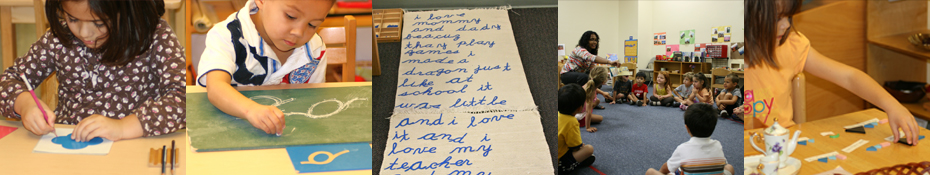

- Search for beauty and don’t settle for less. In Montessori, we surround our students with beauty, from the clean lines of our natural wood furniture, to the delicate porcelain bowls in the Practical Life area, to the art work hung at child’s height in class. Let the same sense of beauty be your guide as you choose books: look for illustrations that are realistic and detailed, not cartoonish and simplified. For a 2- or 3-year old, much of the learning from picture books comes from the pictures. Real art illustrations or beautiful photography will add to your enjoyment of the books you read, and, over time, will elevate your child’s taste, too. We’ve put together a collage of favorite picture book pages here, so you can get a feeling for how visually pleasing these carefully chosen books can be.

- Broaden your horizon. While I select individual books based on their unique appeal, over the years I also strive to expose my children to the world via books. We read about different settings (cities, beaches, forests, mountains, space, the US, China, Japan…), times (pre-history, ancient times, the past century, today), different beings (animals, plants, human beings in different societies and of different ages), different types of stories (historical fiction, non-fiction, poetry). These virtual journeys around the world give us a lot to talk about—and, without an explicit effort on their part, provide children with a wonderful bounty of vocabulary and background knowledge they will draw on later in their lives.

- Make sure you enjoy the books you buy. I saved the best for last: when you preview a book in the store, via Amazon or in the library, make sure it appeals to you! If you don’t enjoy it, you won’t like reading it over and over again. I’ve made the mistake to buy books I didn’t like (usually books that violated one of the first three points above!), and found myself reluctant to read them. And, yes, I’ve even hidden away some of these books, to avoid feeling reluctant when my children bring them to me to read!

Following these guidelines, I’ve put together two starter book lists, one for toddlers and younger preschoolers, and one for older preschoolers and younger elementary children. These books are personal favorites in our family, collected over time and based on recommendations of many knowledgeable teachers and parents: they are books we treasure and couldn’t imagine not having read to our children.

Enjoy!